Josef Hoffmann’s Vienna

Josef Hoffmann’s Vienna

Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art

1201 Bannock Street, Denver, CO 80204

January 21-April 3, 2022

Museum Admission: Free for Kirkland Museum members; $10 general admission (ages 13+); $8 for seniors (age 65+), teachers, students (ages 13+), and active-duty military personnel with ID.

Review by Ashten Scheller

Walking into the temporary exhibition space now housing Josef Hoffman’s Vienna, I am enveloped in a softly playing but lively waltz. The music creates the illusion that I’ve stumbled upon Josef Hoffmann’s (1870-1956) own turn-of-the-century environment. The Kirkland Museum has cleverly made the entire playlist available to visitors with a QR code near the entrance. This soundtrack is comprised of early 1900s Viennese cabaret music and provides an element of sensory education. After all, Vienna was the home of the musical Strauss dynasty, Gustav Mahler, Mozart, Schubert, and Haydn, among others.

Furniture designed by Josef Hoffman in the Josef Hoffmann’s Vienna exhibition, including from the left: Seven Ball Chair (No. 371), designed c. 1906, beech and mahogany woods, manufactured by Jacob & Josef Kohn (1850-1914); Nesting Tables (no. 986), designed 1905, beech wood, manufactured by Jacob & Josef Kohn (1850-1914); Table attributed to Hoffmann, designed c. 1907, beech wood, probably manufactured by Gebrüder Thonet (1853-present); and on the far right: Table, designed c. 1907, wood, probably manufactured by Gebrüder Thonet (1853-present). Image by Ashten Scheller.

It’s clear that great attention to detail and careful planning have been put into the exhibition. One of the key elements of the period and of the Vienna Secession in particular—the notion of Gesamtkunstwerk—is in its very definition. The German term describes “a total work of art,” with the “it” perhaps referring to an entire room, or even an entire building, like Hoffmann’s most recognizable architectural work, the Stoclet Palace (located in Brussels and constructed between 1905 and 1911). [1]

Seven Ball Chair (No. 371), designed c. 1906 by Josef Hoffmann (1870–1956), manufactured by Jacob & Josef Kohn (1850–1914), Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art collection. Image courtesy of the Museum.

These sumptuous twentieth-century spaces exude a playful theatricality, celebrating not only sight, but sound and taste. Hoffmann carefully designed every aspect of a room: the chairs—such as the Seven-Ball Chair on display at the Kirkland—the wall décor, and even the tea sets were hand-crafted, showcasing a fundamental prioritization of hand-made pieces over the growing market of mass-produced, machine-made products in the early twentieth century. Hoffmann is noted as even having gone as far as to design ladies’ dresses to avoid clashing with their surrounding environments. [2]

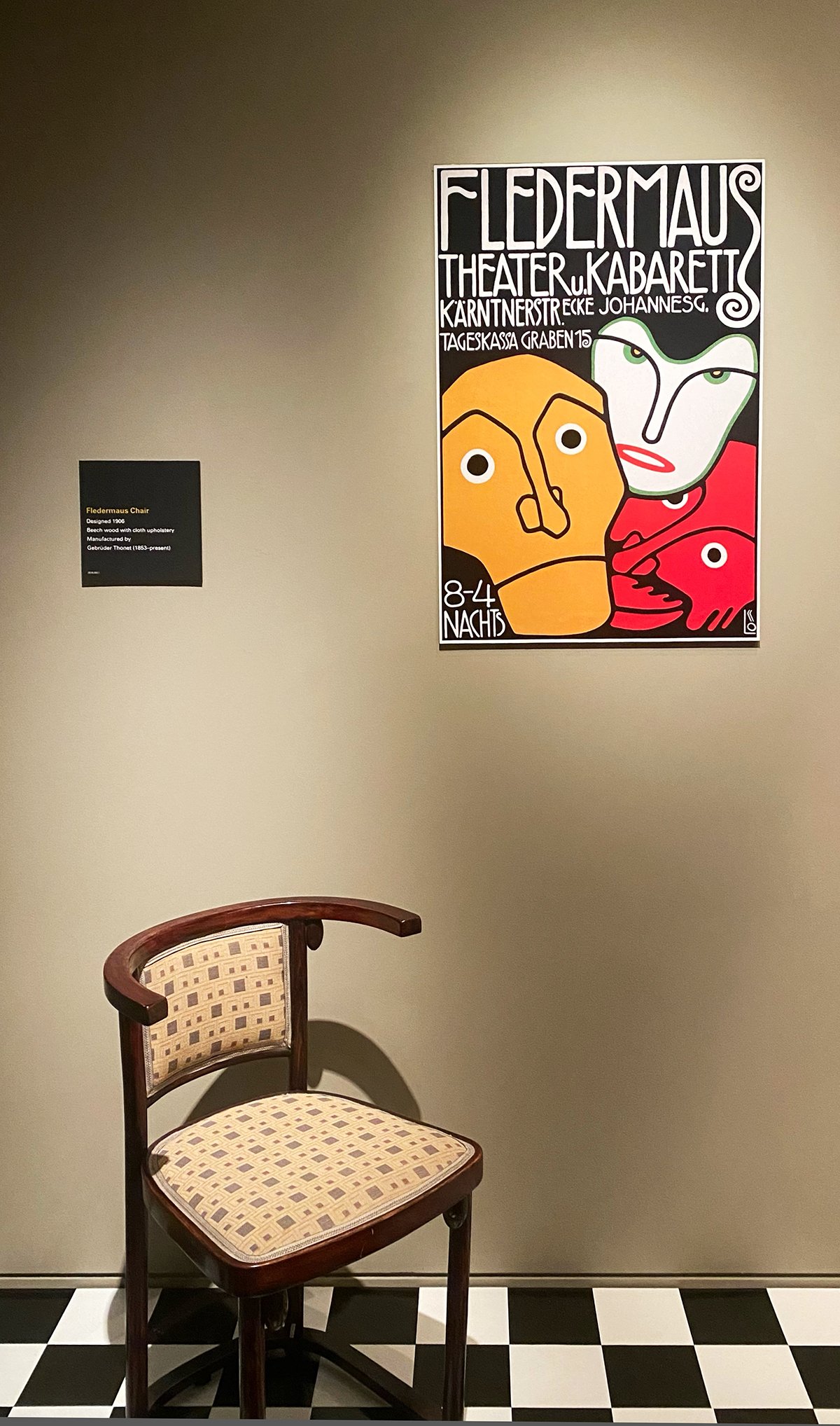

Fledermaus Chair, designed by Josef Hoffmann in 1906, beech wood with cloth upholstery; manufactured by Gebrüder Thonet (1853-present); Right: Fledermaus Cabaret poster. Image by Ashten Scheller.

The most compelling example of this notion of Gesamtkunstwerk in the exhibition is a partial replica of the Cabaret Fledermaus. An underground space that opened in 1907, it included a bar and auditorium, and hosted various performances such as poetry readings, satirical plays, music, shadow puppetry, and dance. All of the senses are valued equally in an immersive experience, which is extended to the viewer not only through the Hoffmann-designed table and chairs, but through a physical copy of the Cabaret’s original 1907 menu. [3] Visitors to the museum are able to imagine themselves as Hoffmann’s eccentric patrons as they approach the Fledermaus Chair and checkerboard tile setting.

I’m pleasantly surprised (and impressed) to discover that all of the artworks have been selected from the Kirkland Museum’s own permanent collection, showcasing both new acquisitions and fan-favorites. Hoffmann’s nickname, “Square Hoffmann” (Quadratl Hoffmann), is evident throughout the space. In contrast with the curving botanical motifs most often associated with the international Art Nouveau style, Hoffmann instead emphasized simple geometric patterns, particularly the aforementioned black and white checkerboard motif.

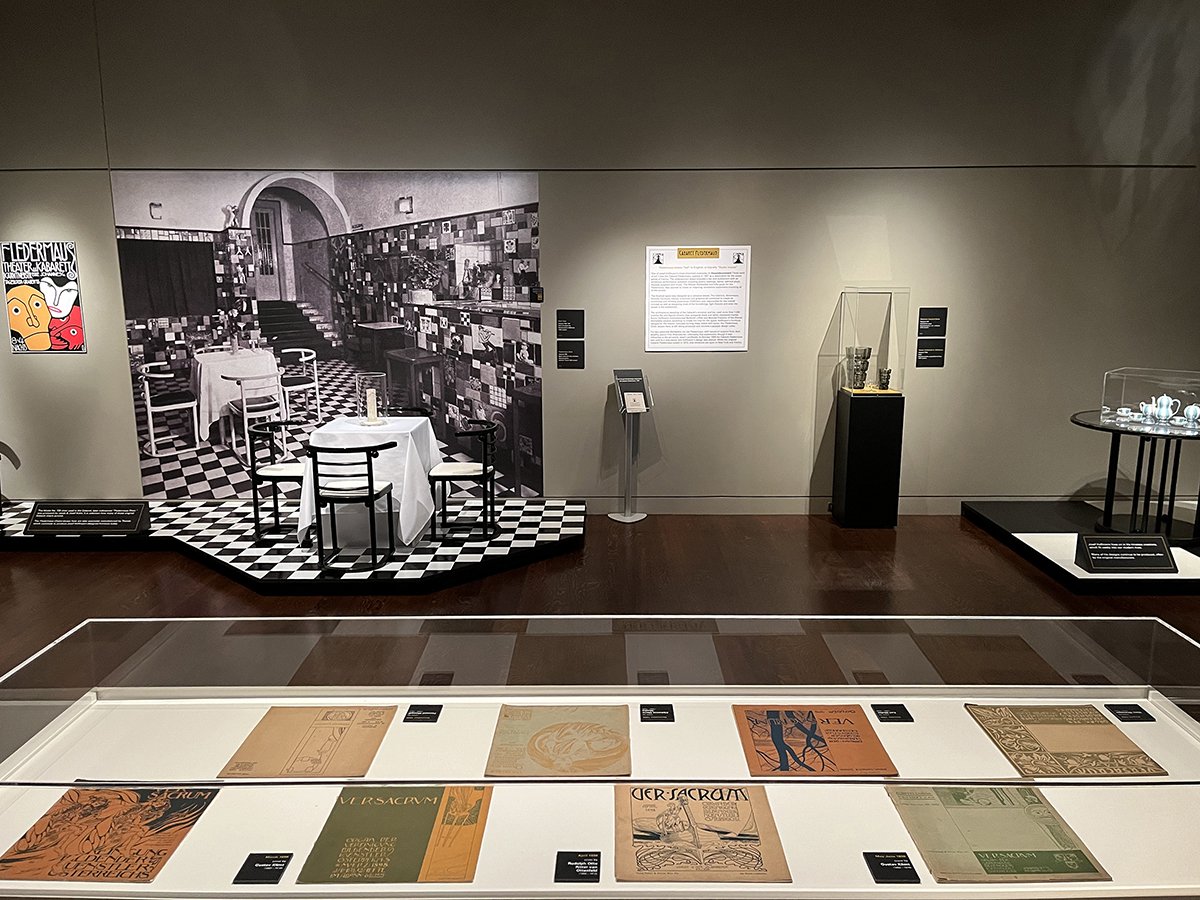

An installation view of Josef Hoffmann’s Vienna with issues of the Ver Sacrum publication in the foreground. Image courtesy of the Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art.

Issue Number One of Ver Sacrum, 1898, cover by Alfred Roller (1864–1935), Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art collection. Image courtesy of the Museum.

Equally as important as the furniture pieces are the many editions of Ver Sacrum on display. This was the periodical printed by the Vienna Secession artists’ group to promote their design philosophies. Such philosophies rejected the elitism of traditional academies and past styles, and instead embraced new, modern, avant-garde styles and motifs. These beautifully illustrated periodicals are cleverly displayed in a checkerboard pattern, once again mirroring Hoffmann’s motif, and they include works not only by Hoffmann but by his well-known contemporaries such as Kolomon Moser, Gustav Klimt, Ritter von Ottenfeld, and Fernand Khnopff. As many as fourteen different copies of Ver Sacrum are on view, which is a sensational number to have in one place outside of Vienna itself.

A photographic portrait of Josef Hoffmann in 1903. Image courtesy of the Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art.

I am left curious about the larger historical context within which Josef Hoffmann was a player. What was his relationship with the larger Austro-Hungarian Empire during this period of his earlier works? When Hoffmann was born in 1870, his hometown of Pirnitz was considered part of Moravia—a region of the Empire in what is now the Czech Republic. [4] The Empire, like many others, was dissolved after World War I. It was split into the individual states of German Austria, the Kingdom of Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and the State of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs, to name but a few. [5]

A view of the Fledermaus Cabaret (1907-1913) furniture and poster as well as a photograph of the interior of the original building in Josef Hoffmann’s Vienna at Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art. Image courtesy of the Museum.

Also, the importance of World’s Fairs during this time—such as the 1904 pavilion in St. Louis, Missouri—cannot be understated, given that they served as platforms for both international competition and exchange. Though the exhibition focuses on Vienna, I can’t help but wonder what effects Hoffmann’s designs had outside this glittering city, as part of a larger international modernist style.

In the end, Josef Hoffmann’s Vienna is a delightful experience, transporting visitors to this glittering period of avant-gardes and refined luxury. Historical detail is widely accessible, and the curation has been thoughtfully accomplished. Over a century has passed since Hoffmann’s revolutionary designs first entered the public eye, and the Kirkland Museum is a superb destination for some much-needed contemplation and escapism into the past.

Ashten Scheller is a Denver-based art historian, writer, and researcher, as well as a volunteer assistant editor for the intersectional online arts platform Femme Salée. She holds a BA in Art History and International Studies from the University of Denver and a Master’s degree in Art History, Theory, and Display from the University of Edinburgh.

[1] Images and details of the Stoclet Palace are available through the UNESCO Heritage Site website at https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1298. This definition of Gesamtkunstwerk was taken from the wall text within the Josef Hoffman’s Vienna exhibition space.

[2] For more on the particulars of Hoffmann’s interior design strategy--including his specificity for ladies’ apparel—see Mark Taylor and Julieanna Preston’s Intimus: interior design theory reader. Chichester: John Wiley, 2006.

[3] This information about Cabaret Fledermaus’s functions was taken from the exhibition wall text.

[4] This biographical information about Hoffmann can be found on the Neue Galerie’s website, at https://www.neuegalerie.org/collection/artist-profiles/josef-hoffmann. Many of Hoffmann’s works are on display at this museum, and at many others around the world.

[5] For more information about the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, see: Andrea Stangl, "The successor states to the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy," habsburger.net. Retrieved January 31, 2022.