Armor

Armor

Center for Visual Art, Metropolitan State University

965 Santa Fe Drive, Denver, CO 80204

July 30-October 16, 2021

Admission: Free

All gallery text available in both English and Spanish

Review by Ashten Scheller

It isn’t often that an exhibition of so many artists (nine, to be exact) is able to cohesively address a theme as broad as “armor”—but the current show at the Center for Visual Art (CVA) does just that. Perhaps the repetition of the word “unprecedented” over the last year and a half was an impetus for the theme, and how it has us reaching for stable, protective measures. In a time of such uncertainty, the warding off of threats is a comforting, sometimes necessary response.

Arms and armor have been present in virtually all cultures for millennia, not only for conquest or protection but for pageantry, ceremony, and individual expression. [1] The CVA gallery space is adorned with bold pieces, organized by artist, which explore the ways each individual (or duo) conceptualizes bodily protection, or the failure of such protection in the face of an array of threats. This thread is strong throughout, though exactly which threats the artists address varies widely, resulting in a stunning, thought-provoking, impactful show.

A view of works by Sammy Seung-min Lee on display at the Center for Visual Art, including Lee’s three Mamabot sculptures on the back wall, from 2020-2021, comprised of picture frames, digital archival prints, silk flowers, hanji paper, and acrylic varnish. Image by Anthony Camera, courtesy of the Center for Visual Art.

Sammy Seung-min Lee, detail of Mamabot - Ms. Daegu, 2020, picture frames, digital archival prints, silk flowers, hanji paper, and acrylic varnish. Image by Ashten Scheller.

Many of the pieces are inherently identity-based, such as those of Sammy Seung-min Lee. Her works reflect on her personal history, often containing found objects and images related to immigration, a sense of belonging, and motherhood. Her Mamabot wall pieces (of which there are three) each take the form of a robot figure, but are covered in her signature paper covering. This “paper-skin” is the result of a laborious, cathartic process, one in which she transforms a fragile material into a tough, leather-like skin, full of textures and scar-like markings. The motherly figures appear to protect the found objects and images beneath their skin, both guarding and displaying their interiors.

Where Seung-min Lee’s pieces exude resilience and transformation, Skyler McGee employs sensitive, delicate textiles in her creation of intimate, interactive pieces. Mother Bodies (2021) is a play on the word “knit,” addressing the need for a communal army and shared experience. The work is comprised of various fabrics, each one a self-contained unit like an individual body, while simultaneously the fabrics are connected to one another as they stand side-by-side, representing the larger fabric of society that unites us all.

Above and below: Skyler McGee, Hide , 2021, paper, encaustic, and textiles on fabric. Images by Ashten Scheller.

Hide (2021) functions as both a verb and a noun: it is a covering to be donned (like a protective cloak or cocoon made from the skin of an animal) just as much as it is a verb and an invitation: enter here, and you will be protected. The work invites the viewer to literally leave behind their burdens, prayers, and longings within the sculpture by writing them on pieces of paper, then inserting them into the hanging piece’s network of honeycomb-like nooks. Armor here becomes a sanctuary.

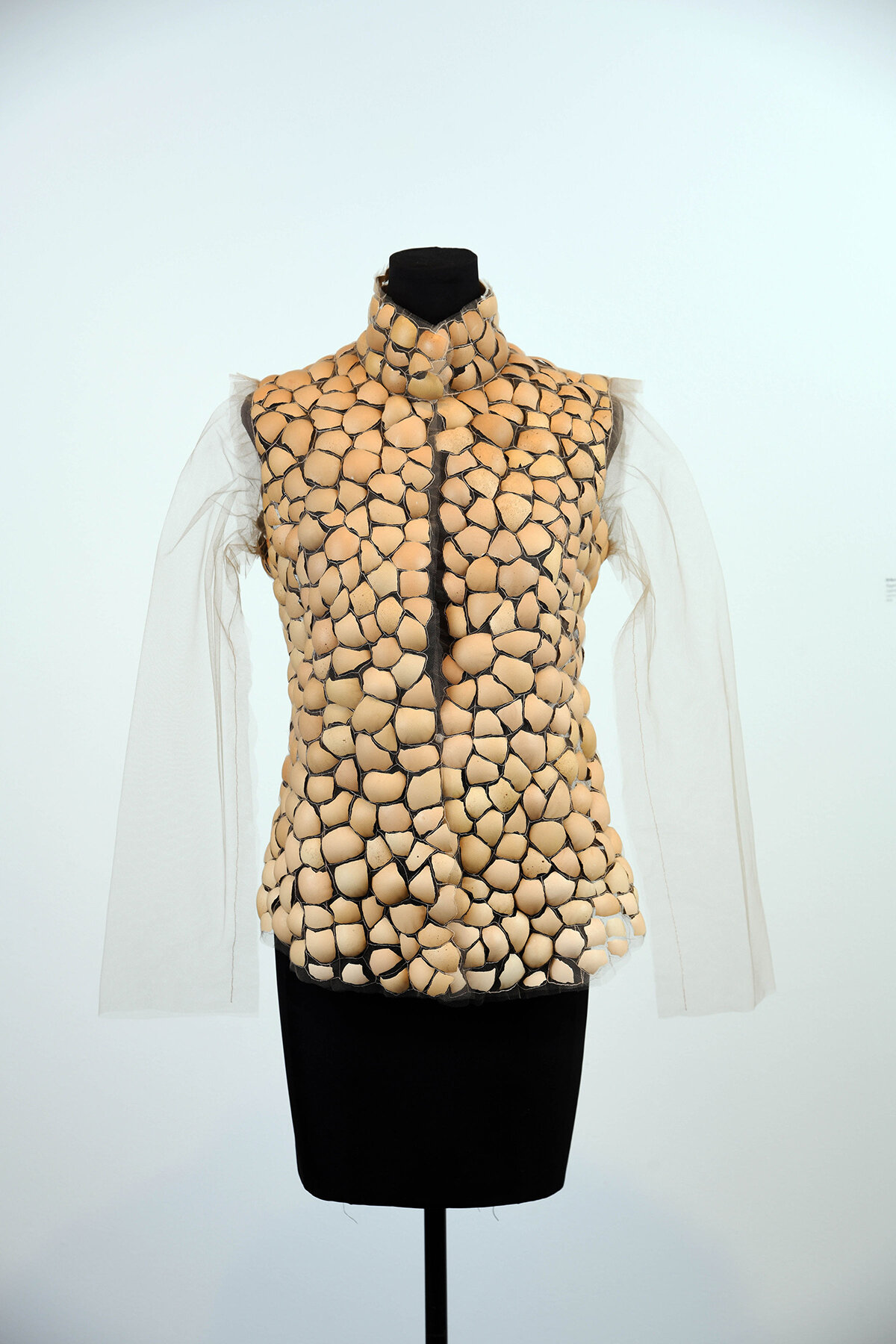

Erika Diamond, Eggshell Shirt for Hugging II, 2016, eggshells, tulle, thread, and dress form. Image by Anthony Camera, courtesy of the Center for Visual Art.

Erika Diamond’s interpretation of the delicacy of existence is viscerally tactile. Her Eggshell Garments (2016) consist of actual eggshells woven together with tulle netting into recognizable items of clothing, making it clear that any impact will be recorded by breakage. All touch here will be commemorated, just as our skin and our bodies record our encounters with one another. Imminent Peril - Queer Collection (2020) alludes to a more specific, violent event: the 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting. Made from bullet-proof Kevlar material, these garments were made to physically shield Diamond’s “queer-identifying friends, lovers, mentors, and artists [she] admires” and advocate for the safety of the LGBTQ+ community. [2]

Above and below: Steven Frost and Frankie Toan, Denim on Denim, 2021, upcycled denim, metal studs, acrylic paint, nylon thread, rhinestones, wood, paracord, and found materials. Images by Anthony Camera, courtesy of the Center for Visual Art.

Similarly, Steven Frost and Frankie Toan’s collaborative piece Denim on Denim (2021) is a striking focal point (visible from the gallery entrance) consisting of several denim-clad shield forms suspended from the ceiling. Inspired by queer denim fashion histories—as denim has historically been worn to signal membership in specific queer subcultures [3]—the artists sourced the denim from their own wardrobes as well as those of their family members, friends, and local thrift stores. In combination with their arrangement that mimics a combat shield wall, the overall installation is a powerful statement: we are stronger together than alone, and our mutual protection promotes individual self-expression.

Merritt Johnson’s works also focus on collective harm and protection, but in relation to our “broken interactions with land, water, bodies, and living culture.” [4] Her works are multidisciplinary and layered, embodying her own personal multiplicity as an indigenous artist (her heritage is a mixture of Kanienkehaka (Mohawk), Blackfoot, Irish, and Swedish) as well as the complex threats facing land, water, and indigenous and immigrant bodies.

A still image of Merritt Johnson, Exorcising America: DIY Safety Ladder for emergence, migration and escape, 2019, single channel video. Image by Ashten Scheller.

Through her video works, Exorcising America: DIY Safety Ladder for emergence, migration and escape (2019) and Exorcises for Global Health: Breathing Exercises series, Johnson guides the viewers through meditations and therapeutic actions as she displays breathing techniques and rips the seams of an American flag to then tie a fabric ladder together out of its pieces. The symbolism refers to the very literal fabric of our society, and whom it has historically protected and harmed, but gently invites the viewer to safely participate. Her sculptural pieces, too, connect directly to the harm associated with borders and frontlines, which function to separate people and erode natural resources. [5]

Works by Jennifer Pettus on display at the Center for Visual Art. Image by Anthony Camera, courtesy of the Center for Visual Art.

Jennifer Pettus’s colorful mixed-media pieces also embody the relationship between materials and their users, specifically in the ways that textiles protect their wearers and take on their own histories of use. Her whimsical, sometimes grotesque sculptures such as Dicky (2017) and Feathering (2015) are comprised of such items as dental floss, masking tape, dressing pins, hair nets, and dryer lint (among many other objects and materials) that are so often discarded. Here, the artist has given them new life as talismans, costumes, and toys. For Pettus herself, the mending of these textiles and household objects is a form of “self-preservation,” with the repetitive work keeping her “sometimes debilitating anxiety at bay.” [6] Both object and process are renewed and renewing.

Ravi Zupa, MT - MMG - 1, 2019, typewriter, bookbinder, and stapler components. Images by Ashten Scheller.

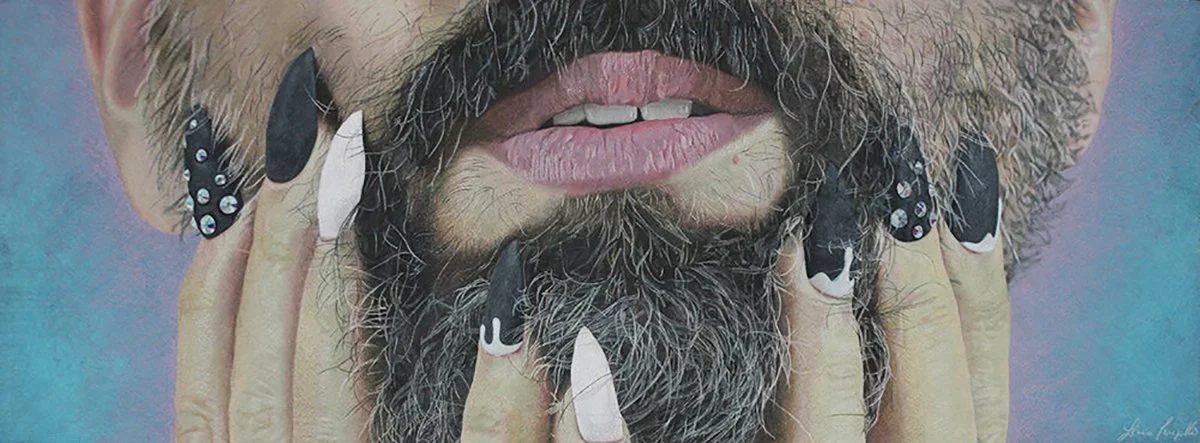

The fantastical is also at play in the work of Ravi Zupa and Jaime Molina. Zupa’s pieces incorporate detailed historical elements, such as traditional printmaking—connecting his work to German Renaissance and Japanese woodblock printmakers—and revolutionary propaganda, evident in his Compound Interests Series (2018). More outwardly threatening are his sculptural pieces such as MT - SMG - Royal 1 (2019) and MT - MMG - 1. At first glance, these objects appear to be actual guns and war machinery, but upon closer look we discover that each is a combination of weaponry and writing devices such as typewriters, staplers, and pen nibs. Each sculpture represents not only physical harm and protection, but the potential harm and protection of words, laws, and ideals.

Jaime Molina, threnody thursdays, 2019, acrylic on found wood. Image by Anthony Camera, courtesy of the Center for Visual Art.

Molina, recognizable around Denver for his mural work, has several beautifully whimsical sculptures exploring the calmness of the protected; many of his pieces, like threnody thursdays (2019) are serene reflections on death. With “threnody” referring to an elegy or “song of lamentation for the dead,” Molina’s figures ask us to question what we deem worth protecting—even beyond death itself. [7]

Armor succeeds in captivating its audience through both comfort and disquiet. The exhibit conveys a diverse commentary on figures and objects that wear armor and why the vulnerable interior is worth protecting. It is both preventative and reflective, posing questions like: what kinds of harm, violence, and attacks have already occurred? What can be stopped, reversed, mended, and healed? Though defensive in nature, the show is not impenetrable to the viewer—all are welcome here.

Ashten Scheller (she/her) is an art historian, writer, and researcher based in Denver. Her scholarship focuses on the intersection of art with (inter)national politics, accessibility, display methods, restitution, mythology, and otherness. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Art History and International Relations from the University of Denver, and in 2020 she completed her master’s degree in the History of Art, Theory, and Display at the University of Edinburgh.

[1] For more information about the role of arms and armor throughout history, see: https://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met/collection-areas/arms-and-armor.

[2] From Erika Diamond’s statement in the gallery.

[3] Some examples include the “clone” look of white gay men in the U.S. in the 1970s, “Gay Jeans Day” on college campuses, and lesbian appropriation of men’s blue jeans.

[4] From Merritt Johnson’s artist’s statement.

[5] See Johnson’s pieces Fancy Shawl for the Frontlines (2020) and Border Breaker (2020), as well as her own description of these pieces on her website at https://flashbanggiveaway.com.

[6] From Jennifer Pettus’s artist’s statement.

[7] Definition of “threnody” from the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/threnody.