Tools of Conveyance / Staring into the Fire

Tim Whiten: Tools of Conveyance

Kate Petley: Staring into the Fire

CU Art Museum, University of Colorado at Boulder

1085 18th Street, Boulder, CO 80309

August 17-December 18, 2021

Curated by Sandra Q. Firmin

Admission: Free

Review by j. gluckstern

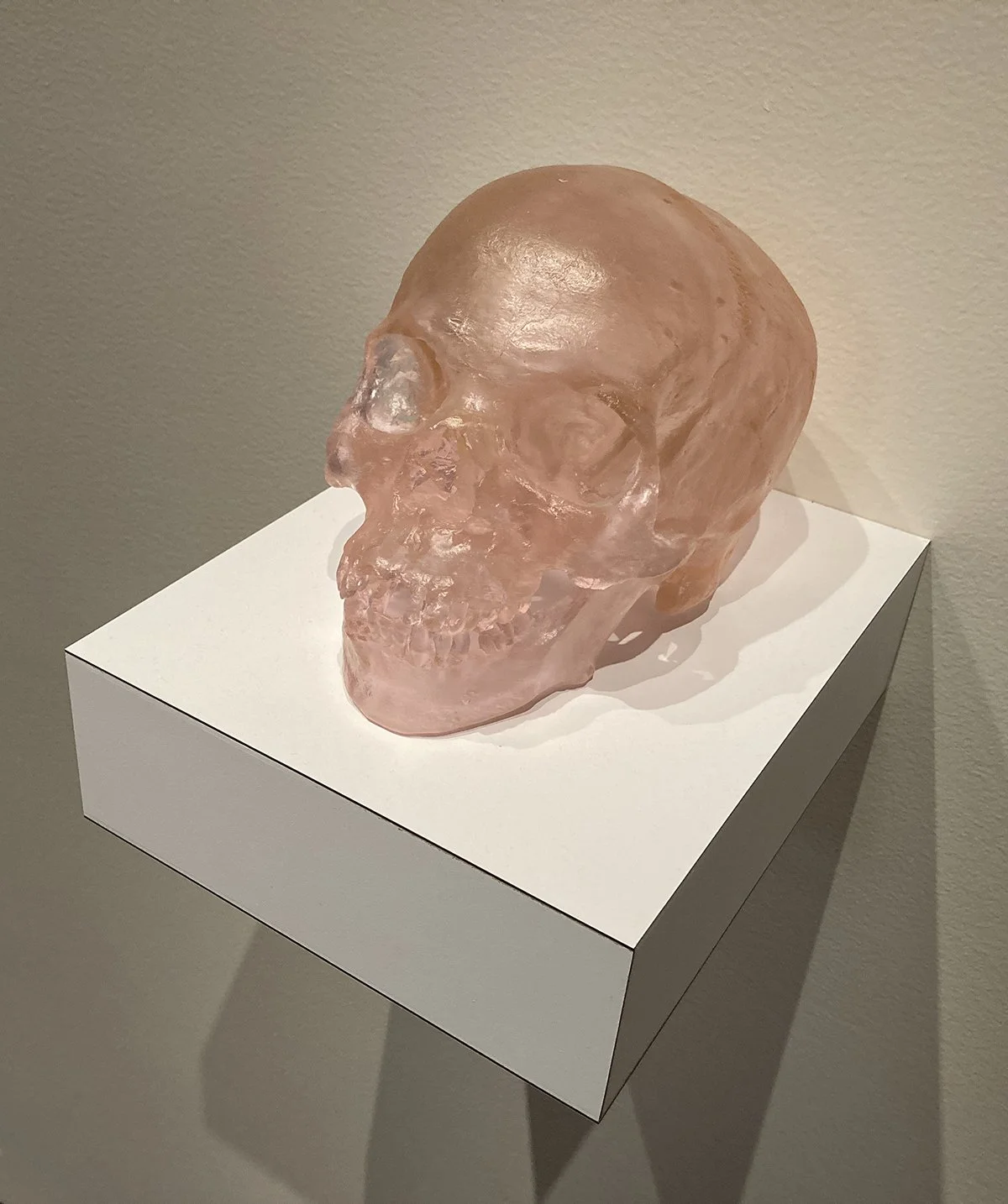

A luminous, violet-hued skull greets viewers as they enter Tim Whiten’s exhibition Tools of Conveyance—a retrospective of work from the last 40 years—at the University of Colorado Art Museum in Boulder. While Whiten has utilized real human skulls in his work, this piece—Perceval—is fashioned only from lead crystal glass. [1] But as a touchstone for themes of presence, identity, and mortality, Whiten’s transformation of this multifaceted symbol acts as a bridge to the subtle but profound investigations beyond.

Tim Whiten, Perceval, 2013, lead crystal glass, courtesy of the artist and Olga Korper Gallery, Toronto. Image by j. gluckstern.

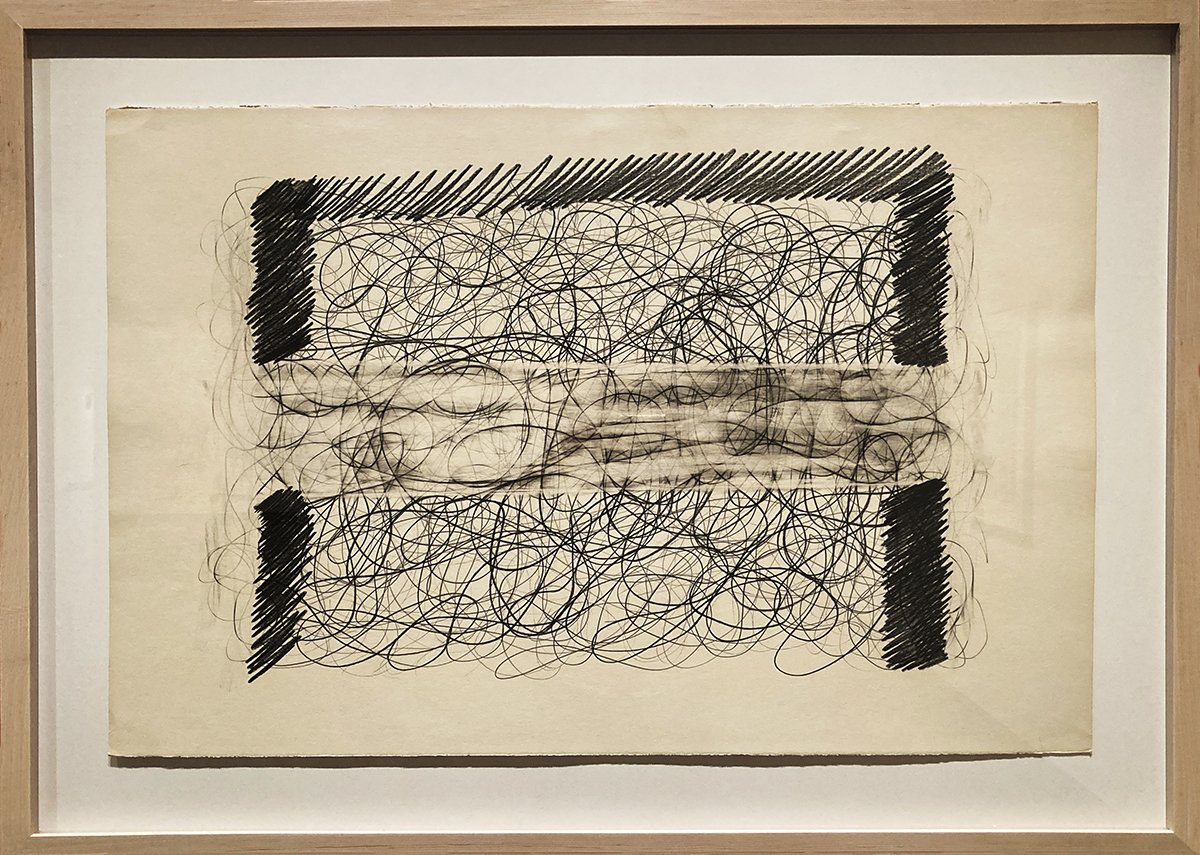

IDY Space, a grid with tiny red hearts inside each square, uses another recognizable symbol—the heart—to connect with the viewer. Whiten highlights each heart with white acrylic paint and stains them with lemon juice, at once isolating the hearts and suggesting a solid presence built from repetition. Nearby, Spanner, drawn with graphite on paper, repeats looped scribbles bound by a dark band of continuous, spiny, diagonal marks. A swath of partially erased graphite divides the piece horizontally. The scribbles become a symbol in themselves—of play, of dedication to the “rules” of a particular piece, and of a desire to communicate in unconventional ways. Whiten’s work side-steps direct address in favor of oblique but powerful languages.

Tim Whiten, Spanner, 1975, graphite stick and graphite pencil on paper, courtesy of the artist and Olga Korper Gallery, Toronto. Image by j. gluckstern.

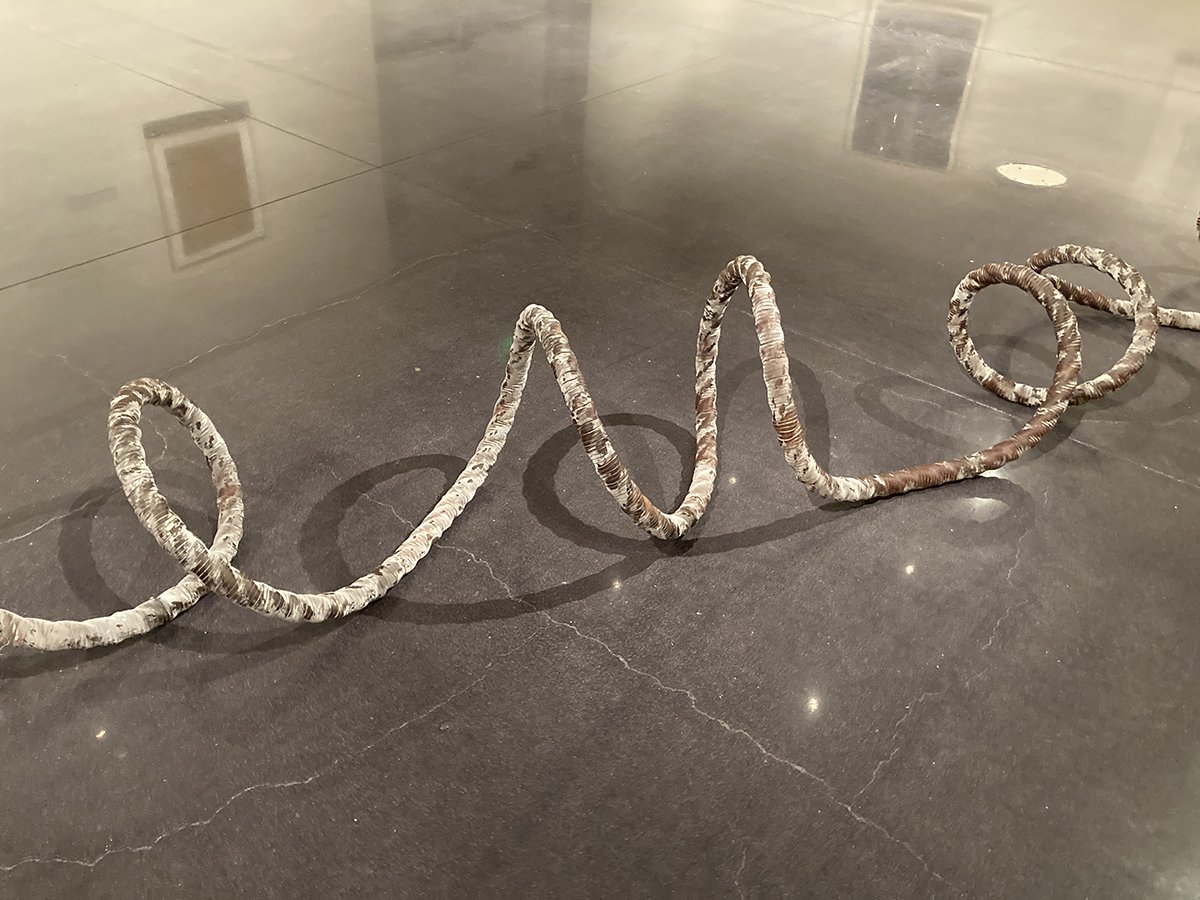

In some pieces, those languages take on the form of written words, such as Page from the Book of Light, Feeling and Knowing, I, with its scribbled “sentences,” or Magic Gestures, Lites and Incantations, a pairing of calligraphic tours de force on orange and purple backgrounds respectively. In others, the viewer is drawn into murky worlds just beneath the surface. Hopscotch II is a looming, ominous composition in which Whiten largely obscures his delicate graphite drawings with black enamel spray paint. Bold Blood, which the artist characterizes as a self-portrait, uses black and purple enamel spray-painted strokes to evoke chaotic microscopic realms. [2] And Rope, a three-dimensional work sculpted with hemp fiber and leather, resonates formally with the looped scribbles of Spanner.

Tim Whiten, Rope, 1973, hemp fiber and leather, courtesy of the artist and Olga Korper Gallery, Toronto. Image by j. gluckstern.

Tim Whiten, Enigmata with Rose, no. 20, 1996-1998, coffee-stained cotton hospital sheets, courtesy of the artist and Olga Korper Gallery, Toronto. Image by j. gluckstern.

Rope also acts as a bridge to the other sculptural works. Enigmata with Rose, no. 20, is made up of coffee-stained hospital sheets—the stains elegantly revealing the folds in the fabric created from usage and framing a delicate printed rose. A crystalline broom leaning in a corner—One, One, One, 1—suggests a life of repetition tidying up domestic spaces. In Mary’s Permeating Sign, a piece honoring Whiten’s mother, there is a glass rolling pin etched with a magic square that contains numbers culled from her birthdate. It rests on a white pillow, creating a contradiction between domestic labor and the deserved rest necessitated by it. T after Tom is an elaborately constructed homage to the artist’s father’s time as builder that incorporates luminescent glass as a key material.

With these works, we share the gallery space with the ghosts of Whiten’s parents. Revisiting a piece like Rope, positioned close to the center of the gallery, it’s not hard to see Whiten’s explorations of personal gestures as a reminder of echoes of those who’ve gone before us.

An installation view of Kate Petley’s exhibition Staring into the Fire at the CU Art Museum in Boulder. Image by DARIA.

Kate Petley’s Staring into the Fire prods us toward different sorts of awareness. Her striking abstract prints and paintings challenge our understanding of surface, depth, color, and representation. Without obvious representational symbols, Petley draws the viewer into a sort of interpretive dance around perception. At first, the effect is like color field painting. Brightly-colored, sometimes arced, sometimes straight-edged forms interact within the frame in one pleasing abstract composition after another. But upon closer examination, it becomes apparent that while the basic forms are photographs of colorful abstract constructions—of cardboard (sometimes smeared with wide brush strokes or globs of paint) and other studio detritus—after making the prints, Petley subtly enhances many of the surfaces with paint.

Kate Petley, Floodgates, 2021, archival print and acrylic on canvas, 48 x 52 inches. Image courtesy of the artist and Robischon Gallery © Kate Petley.

For instance, in a work titled Floodgates the artist diffuses a hard circular edge with acrylic. In Counterclockwise, she uses smudges of paint to soften a simulated point of collision between two boxy forms. In other pieces, like Second Thoughts, a scrape of white paint or a scuffed edge comes straight from the photo, or a photographed shadow suggests depth where there isn’t any.

Kate Petley, Counterclockwise, 2021, archival print and acrylic on canvas, 48 x 52 inches. Image courtesy of the artist and Robischon Gallery © Kate Petley.

Petley also plays with scale, magnifying brush strokes, dried bits of paint, stained paper, distressed surfaces, and torn paper edges far beyond what we can imagine to be their actual size. We are suspended between the promise of clean-lined, abstracted forms and the crush of competing materials, colors, and textures that make up our daily lives. In Petley’s hands, what we experience is a comforting meditation on pure form without denying the tactility of the world.

A view of Kate Petley’s works, from left to right, Difficult Character 4, Difficult Character 3, and Difficult Character 2, 2020, acrylic on altered cardboard, 70 x 108 inches, 38 x 42.5 inches, and 38 x 42.5 inches. Image by Wes Magyar, © CU Art Museum.

Difficult Character 1, 2, 3, and 4—a grouping of four works in a shadowy side gallery—give us a sampling of the materials and textures in the original assemblages. We can see the true dimensions of the objects and consequences of soaking cardboard in water as well as staining and tearing it. Like a magician revealing part of the trick, the work in the main gallery becomes that much richer as we consider how photography has flattened and abstracted the original constructions. It’s all part of the artist’s strategy to make us aware of the assumptions we bring to observation when it comes to photographic images, painted surfaces, and textures we can feel. Instead of being cut off from the original materials, we get a glimpse of Petley’s sense of play, wonder, and surprise. It’s a lively place to be, and definitely worth a visit.

j. gluckstern has a checkered past, and he’s leaned into it. Filmmaker, arts journalist, editor, graphic artist, designer of illustrations for online accounting courses, photographer, and teacher are some of his professions. In recent years, on any given day, he's most likely teaching film production at the University of Colorado at Boulder or experimenting with long-exposure night photography in the streets and open spaces of Boulder, Colorado.

[1] I gleaned some insights on Tim Whiten’s practice and past work from an interview with the artist by ArtSync host Lori Starr in 2011. The interview can be accessed via ArtSync’s Vimeo channel: https://vimeo.com/19487237.

[2] From information listed on the title card for the work in the exhibition.