Stephen Shugart

Artist Profile: Stephen Shugart

Foiling the Dark

By Madeleine Boyson

For all its illumination, light is an elusive artistic affair—essential to any visual work yet the source of existential inquiry: Does light exist without darkness? Is it possible to discuss light without diminishing its power or worse, suffering from cliché?

Stephen Shugart—a local author-turned-artist who works in sculpture, installation, and painting—has a unique perspective on light. Using it as paint and poetry alongside natural and human-made objects, Shugart captures transcendent moments of reality to literally illuminate the dark. And while not all of his work features a bulb, the light in and behind Shugart’s visual oeuvre is a narrative foil to darkness, a mechanism for wonder, and a path to self-discovery.

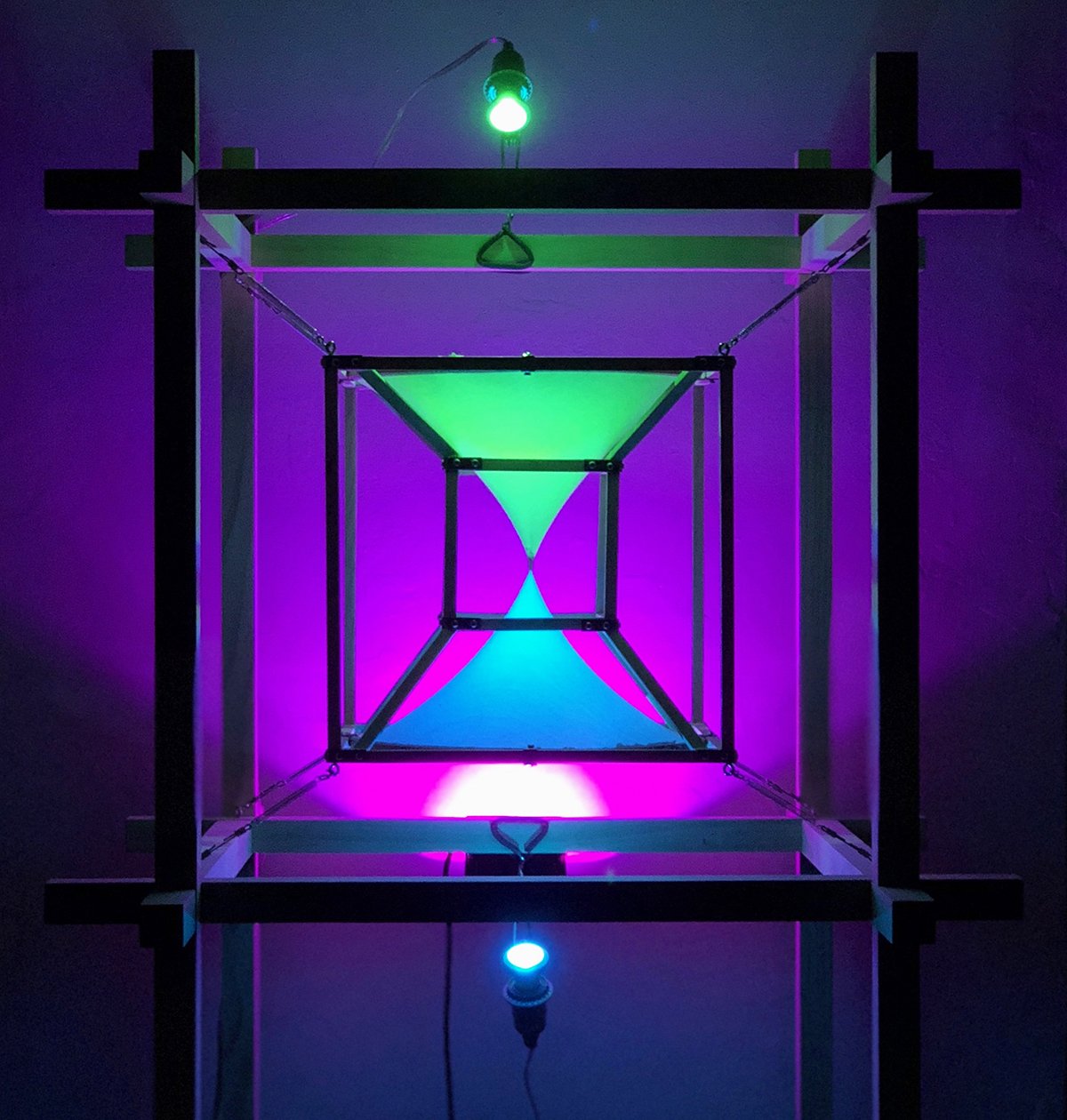

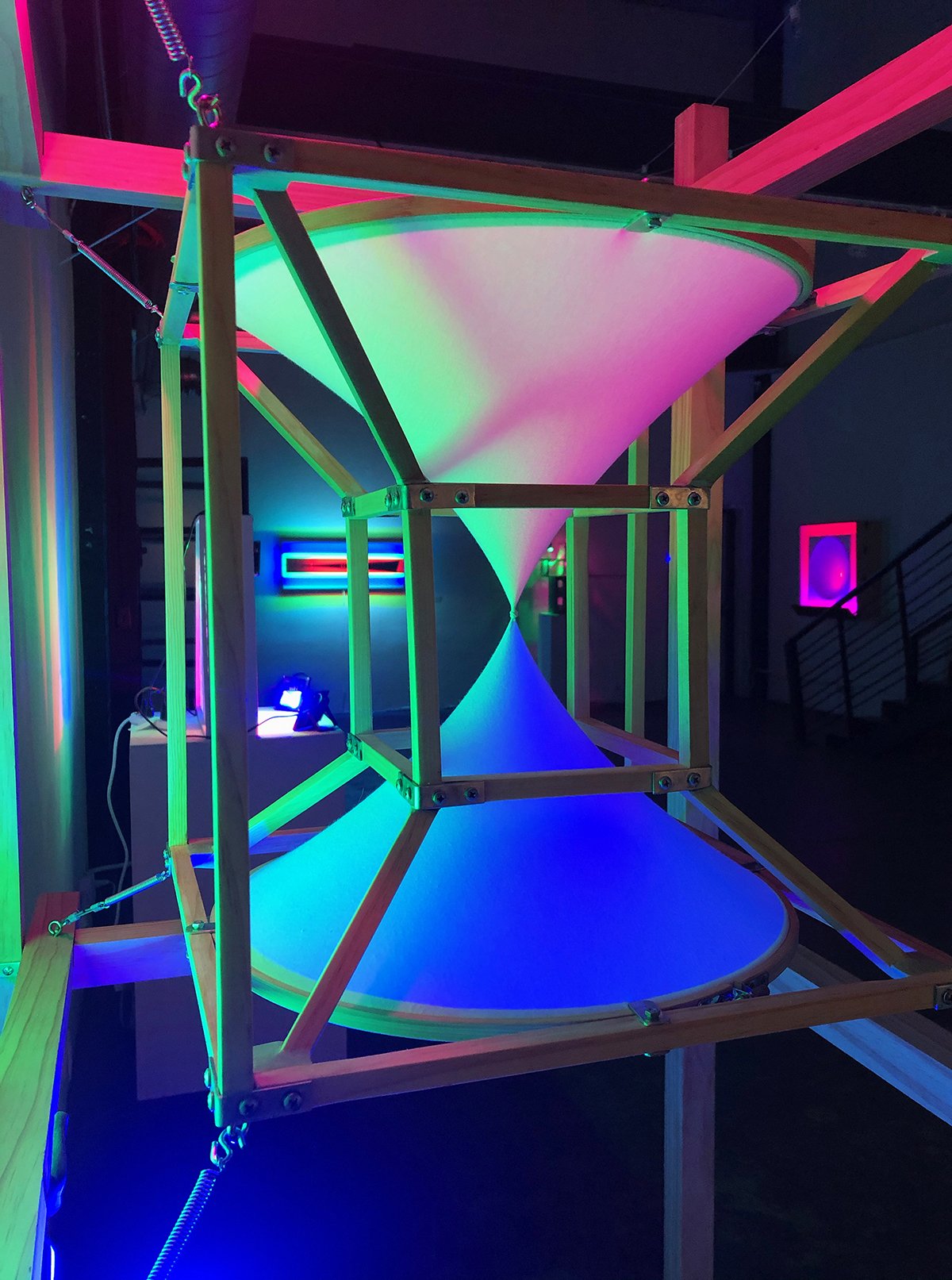

Stephen Shugart, Past, Present, Future, and Elsewhere, 2018, pine, embroidery hoops, polyester spandex, thread, springs, cable, clamp lights, remote control Bluetooth RGB LED bulbs, and hardware, 79 x 36 x 36 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Born in Denver to a Methodist minister mother and a pediatrician father, and raised in Littleton in the 1960s and 70s, Shugart always knew he was an artist. “I simply have a vision…about the world that I am compelled to express artistically, ever since I was a kid,” he says. [1]

But he wasn’t originally a visual creator. As a published writer, poet, produced playwright, and editor, Shugart focused thirty years of committed effort on literature. He received an MFA in creative writing from Colorado State University and later taught college-level writing, composition, and critical thinking courses at over five institutions, alongside jobs in instructional design, house painting, and renovation.

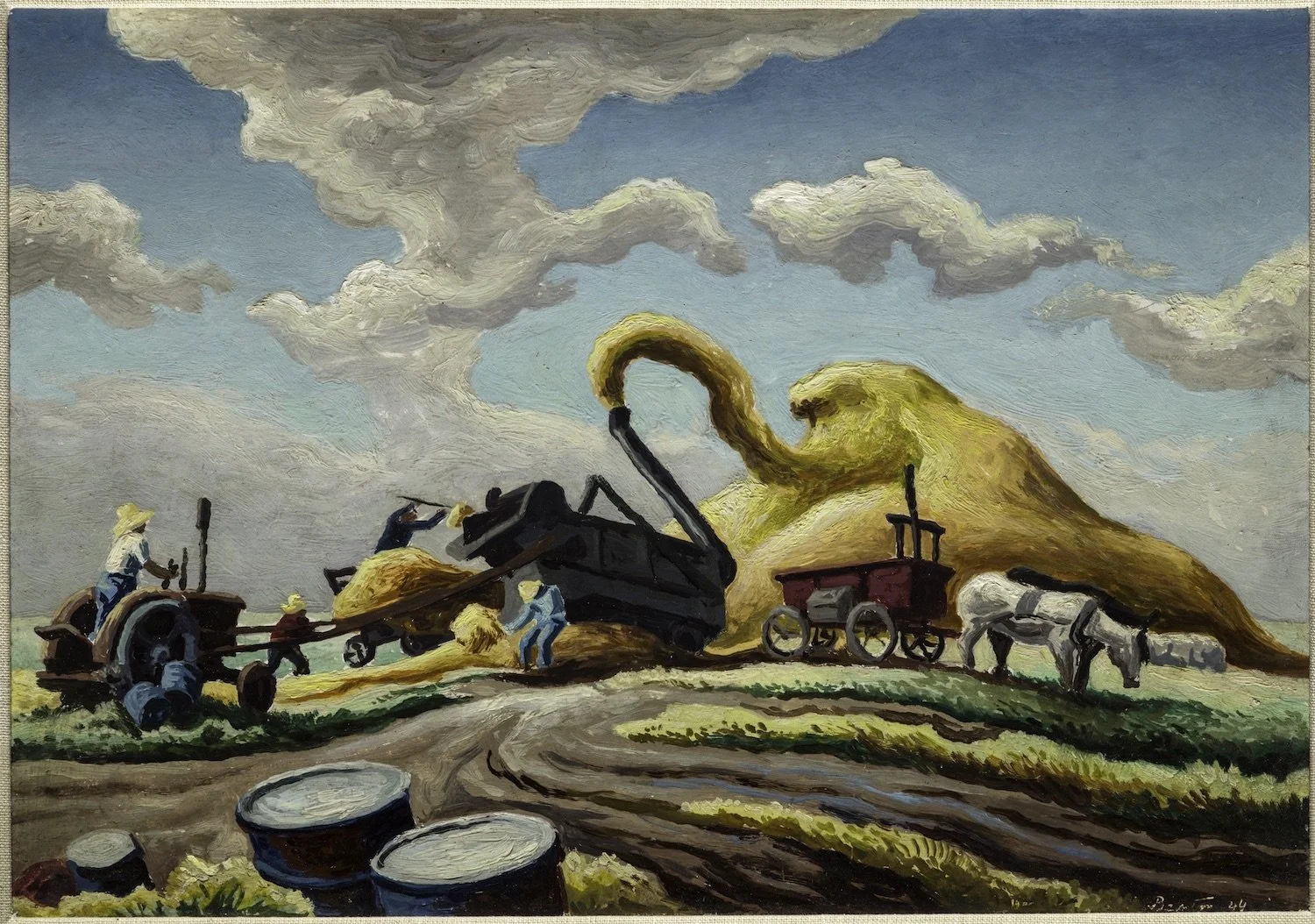

An installation view of Stephen Shugart’s exhibition Enlightenment of the Ordinary at Recreative in Denver in 2020. Image courtesy of the artist.

Through writing, he refined his aesthetics in psychological darkness, dealing with “themes of grief, depression, self-destruction, and suicide, with dark humor and magical realism,” exemplified by his short story collection Dark Matter. [2] Personal tragedy in his thirties furthered this preoccupation, and writing became a “psychodrama” to investigate trauma and pain, even if it never quite became therapy. “I did my best to find other stories and not write about self-destruction and grief,” Shugart says. “[But] it kept coming out somehow in these dark and often sad fictions.”

To counteract this darkness, Shugart began an Introduction to Oil Painting class in the early 2010s and found that not only was the activity satisfying, it might be an unrealized skill. He had already begun questioning the trajectory of his life and writing, and this new craft was the crucial push he required: “I needed to make a big shift and recalibrate—to do what was more natural for me and what was truly me and made me happy… I finally thought, ‘Screw it, I’m going for art’.”

Stephen Shugart, Barracuda View from Unit 2, 2012, oil on canvas, 30 x 40 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

The artist situated his new visual language in a familiar magical realism. His early pieces highlight boats and classic cars in a surrealism that crystallizes with close-looking. Barracuda: View from Unit 2 (2012), for instance, features a blue 1967 Plymouth Barracuda in an underwater mountain range. A submersible, remote-operated vehicle (ROV) spotlights the car under a bending school of fish, foreshadowing the artist’s later interest in light bulb art.

Looking back, Shugart can trace a subconscious interest in painting through his writing: “I now see that I have been mostly interested in setting, not so much plot or characterization, basically painting scenes realistic and surrealistic with words in narrative. So it’s been a long road to visual art.”

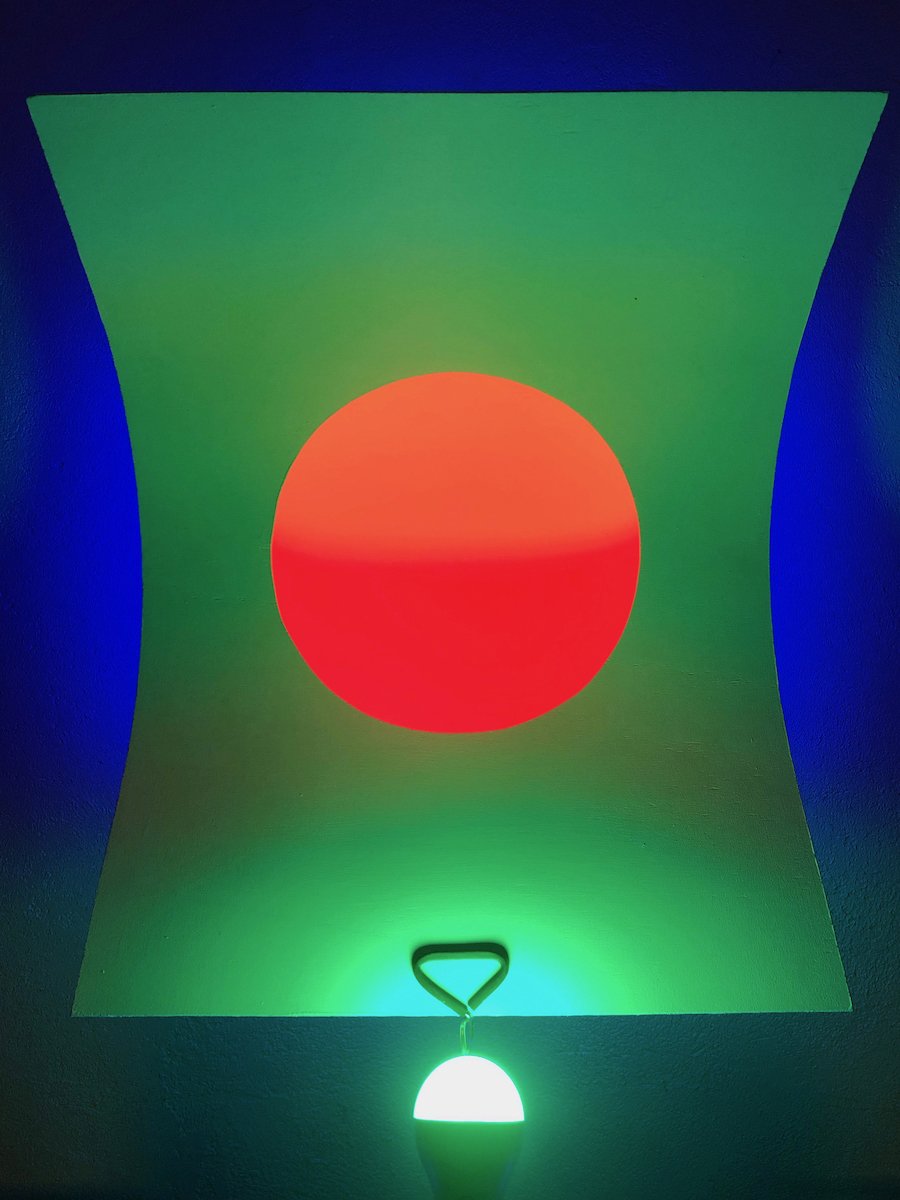

Stephen Shugart, Solar Disc, 2020, 1/8" bending plywood, MDF, remote control LED light strips, remote-control LED light bulb, clamp light, pure white flat house paint, and additional hardware, 22 x 20 x 12 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Then in 2013, the emerging artist saw a Charlie Rose episode on public television that broke everything open. “That was life-changing, eye-opening, one of those moments,” declares Shugart. Rose was interviewing James Turrell (b. 1943), an American “pure light” artist who helped develop the 1960s Light and Space movement in California, which focused on immersive, unmodulated, colored light fields that play with perception and experience. [3]

“[N]ot only was I captivated by his ideas around art, but also him as a person and his amazing body of work,” Shugart relates. “I felt a deep sense of connection, like he was kind of an artistic father.” Turrell had created a formal language for light as an artistic medium, building an aesthetic heritage for artists like Shugart to pick up and make their own.

Stephen Shugart, 4 X 4 Mobile Landscape Viewing Device (a.k.a The Tourelle), 2014, 1987 Toyota 4X4 truck, viewing cowl: plywood, paint, color-changing remote-control LED strips and bulbs, chrome airplane hood ornament, and hardware. Image courtesy of the artist.

Turrell told Rose and PBS viewers about “the light within”—a Quaker concept that resonated with Shugart’s family history and his experiences with transcendental meditation (“the interior…light shows in my brain when meditating”). Shugart flew to Los Angeles to view Turrell’s work in person before beginning the “deeply personal” practice of making “some cool pieces, if just for myself” at his new studio in Denver. [4]

This was Shugart’s homecoming. “I began feeling so liberated with the process and the results… I was finally doing my own thing… It was my life now, and I was literally and figuratively bringing light into my own darkness and the rooms filled with colored light. It had nothing to do with those dark themes in my writing. I escaped…into the light. It was profound.”

Stephen Shugart, Battery Powered Mobile Landscape Viewing Device, 2015, wide view, found picture frame, PVC pipe, plywood, found aluminum stand base, rope, color-changing remote control LED strips, bar stool/chair, and hardware. Image courtesy of the artist.

Some of Shugart’s work reflects the Turrell legacy—the orange circle in Solar Disc’s (2020) green arciform ground is reminiscent of the older artist’s Skyspaces. Shugart’s Landscape Viewing Devices (like The Tourelle from 2014) recall Turrell’s Magnatron Series by framing perspective, beyond the obvious phonetic similarities. And one reference is even explicit: Robert Woods Meets James Turrell (2014) pairs a pre-made print with a Turrell-inspired cut-out analogous to the named artist’s Corner Shallow Spaces.

But Shugart is his own artist, a crucial distinction made clearer by medium. Where Turrell’s installations create a meta-reality in which the work “has no object, no image, and no focus,” Shugart grounds sublime perception in universal materiality, pairing fluorescent colored bulbs with cardboard boxes, prefabricated embroidery hoops, wood, stones, and wire. [5]

Stephen Shugart, Controlled Burn, 2021 1 x 4-inch pine board, cardboard shipping box, river stone, steel cable, remote-control RGB LED light strip, clamp light, remote control RBG LED light bulb, insulation packing rod, paint, graphite, shellac, and hardware, 32 x 25 x 3.5 inches. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Controlled Burn (2021) displays a hot amber disc framed by a grooved veneer and smooth, wooden planks with singed tips. A rock dangles before the poetic fire, evoking the pendulum bob of a grandfather clock. The piece is visceral, yet magical—Shugart prompts his audience to find familiarity in the work, summoning a mystical past or present in which humans retain the capability to harness natural forces.

Stephen Shugart, Past, Present, Future, and Elsewhere, 2018, pine, embroidery hoops, polyester spandex, thread, springs, cable, clamp lights, remote control Bluetooth RGB LED bulbs, and hardware, 79 x 36 x 36 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

In Past, Present, Future, and Elsewhere (2018), the artist frames the intersection of the title spacetimes in concentric cubes made of square dowels. The center cube—suspended by springs—features two embroidery hoops that stretch from a coaxial center, while fluorescent lights illuminate the work from three sides, generating a multicolor gradient. Shugart draws on universal materials to excite wonder in the viewer in this theoretical piece, questioning whether the intellectuality it imbues resonates with the audience’s own experiences.

Indeed, Shugart tells me that his light-based art has led him to study cosmology, quantum physics, and chaos theory. “I have been…deeply curious about the nature of reality, what reality is, if anything, how it changes depending on perspective and emotional states…special moments of beauty and magic…momentary connections to universal experience, positive and negative, light and dark.”

Stephen Shugart, A Little Poem, 2021, fluorescent light bulb, twigs, lamp holder, padauk, uranium glass beads, brass screws, and black light, 10 x 14 x 14 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

A Little Poem (2021) illustrates how the artist’s dark/writing and light/painting feed off each other, informing our concepts of both. A white, unlit compact fluorescent light (CFL) bulb sports at least a dozen twigs radiating from its curved tubes. The unit’s block base features uranium glass beads at each corner, painting subtle glows that shine under a black light. The poetry or playfulness here is in the fact of this work’s darkness. Without this foundation, A Little Poem’s material combination would be bald and static, lacking life and resisting transcendence.

Stephen Shugart, Elegy for Rivers, 2021, cardboard box, marker, remote control RBG LED light bulb, cinder block, and stones. Image courtesy of the artist.

This, then, is a driving ethos for Shugart: if time stretches, loops, or shorts out in joy or tragedy (when we try hardest to make sense of ourselves), it may be possible to capture these moments via light. Shugart subsequently challenges binaries between nature and civilization, ordinary and non-ordinary reality, humankind and the cosmos, as in Elegy for Rivers (2021), a glossy cardboard box perched atop a cinder block. This futuristic carton—hole-punched and robotic—juxtaposes river rocks with alien geometries and asks: “What’s your conclusion? Is this a moment (of transcendence) for you? Does this align with your reality?”

As a result, Shugart’s work reflects the introspection of a visual artist who has finally come to terms with the fact that he is one. “At a basic level, you are either an artist or you are not,” he tells me. “And if you are, you have to live with that and make peace with it.” It is this iterative homecoming, this repeated return to the self that bears out in his injunction that “art is in the doing.” Every time Shugart engineers with photons, he alters and reveals the basic reality that he has, fundamentally, always been an artist.

Stephen Shugart, Big Bangor Bullet, 2019, pine, MDF, spray paint, brass screws, glass fragment, and remote-control LED lights, 18 x 48 x12 inches. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

When I first saw Shugart’s work in person, I noticed how the punchy glow from pieces like Big Bangor Bullet (2019), for instance, sliced through the artist’s dim basement studio in a way that is impossible to capture with words. Writing about art is the collision of two creative disciplines, and you can often say with one what you cannot say with the other. But Shugart shows me how art after writing can be enough, in “those moments when you are suddenly in the ‘zone’:…when you suddenly consider something you’ve never considered before—even fundamentally switching your opinion—…when you fall in love, or realize it’s over, when you are faced with sudden loss and grief,…sensing the infinite, when you are absorbed in the act of creation, a sense of connection to a universal consciousness,…when you see things in a new light.”

You can see some of Stephen Shugart's brand new light work in an upcoming solo exhibition at Edge Gallery from June 24 to July 10, 2022. The show will be held in the co-op's new space in the 40 West Art Hub at 6501 W. Colfax, Lakewood, 80214, and will be preceded by an Edge Gallery group exhibition from May 13 to June 19, 2022, which will also feature a piece by the artist. Visit Shugart's website at www.stephenshugart.com for more photos and descriptions of his previous exhibitions and series.

Madeleine Boyson is a Denver-based writer, lecturer, curator, and artist. Her art and scholarship concentrate on American modernism, natural photography, and (dis)ability studies, including issues of care and dependency as well as the wholeness of the body. Madeleine holds a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Art History and History from the University of Denver and volunteers as Development Director for Femme Salée—an online intersectional platform focusing on complex embodiment in the arts.

[1] All quotes unless otherwise noted come from the author’s email correspondence with the artist in December 2021 and an in-person conversation with the artist on January 2, 2022.

[2] “About,” Stephen Shugart, accessed January 31, 2022, www.stephenshugart.com/?page_id=99; Dark Matter: Stories, published in 2009 by Outskirts Press, is available for purchase on Amazon and at Barnes and Noble.

[3] “Introduction,” James Turrell, accessed January 31, 2022, jamesturrell.com/about/introduction/.

[4] “Enlightenment of the Ordinary,” ReCreative Denver, accessed January 18, 2022, www.recreativedenver.org/enlightenment-of-the-ordinary.

[5] James Turrell, quoted in “Introduction,” James Turrell, accessed January 31, 2022, jamesturrell.com/about/introduction/.