Mutual Terrain

Denver Month of Video (.MOV): Mutual Terrain

RedLine Contemporary Art Center

2350 Arapahoe Street, Denver, CO 80205

July 11–August 3, 2025

Admission: Suggested donation of $5 for adults, $3 for youth and students; free for members

Review by Madeleine Boyson

I first heard about “ecofascism” around the time that COVID-19 hit full force in 2020. Concerned digital citizens were responding to social media posts exclaiming that, in the wake of an “anthropause” (widespread quarantine), Earth was recuperating. Dolphins had returned to Venice’s canals. Air pollution dipped in the absence of motor vehicles. Nature was “healing.” [1]

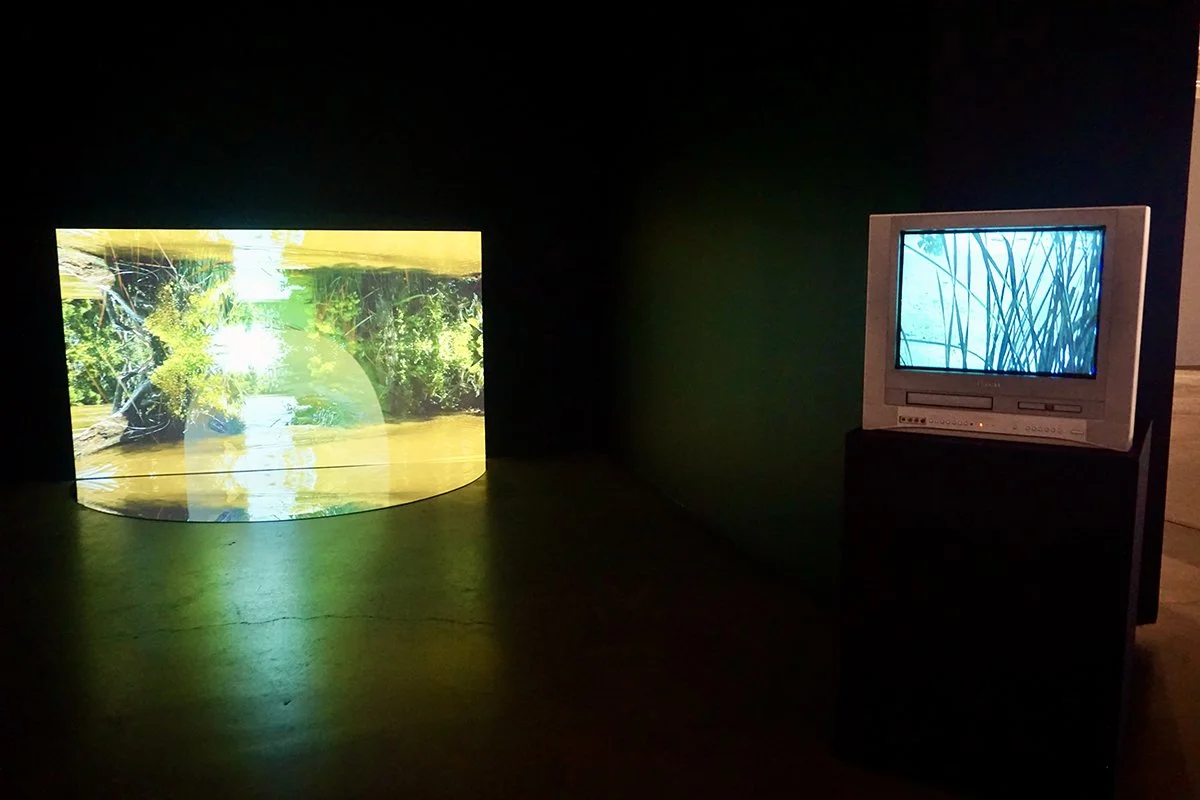

An installation view of Mutual Terrain at RedLine Contemporary Art Gallery, curated by Adán De La Garza and Jenna Maurice, as part of Denver Month of Video (.MOV), on view through August 3, 2025. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Ecofascism “suggests that certain people are naturally and exclusively entitled to control and enjoy environmental resources,” according to Alexander Menrisky. Among manifold ecofascist ideologies is the “misanthropic” message that the Earth is separate from us and would be better without us, thus creating room for eugenicist and genocidal creeds that welcome mass death as a means to curb environmental damage. Though memeifying the unintended consequences of lockdown produced chuckles, it also brought to light a sinister belief about humans as “the real virus”—that we ought not be afraid of SARS-CoV-2, but ourselves. [2]

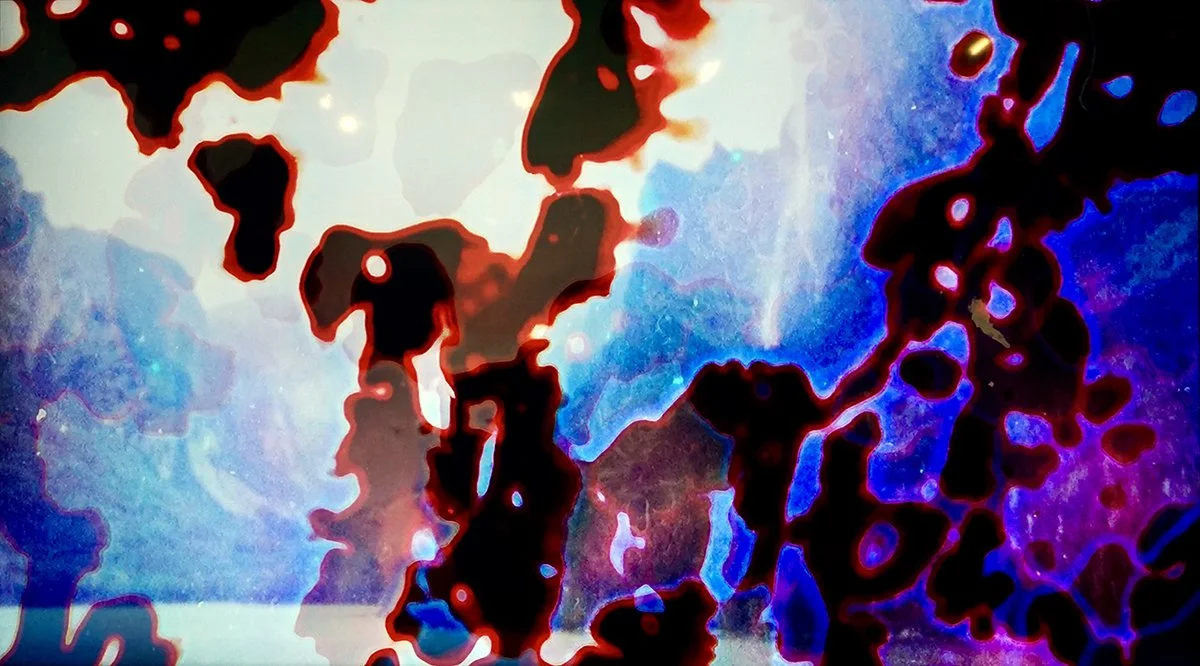

Ella Morton (Canada), still image from The Great Kind Mystery, 2022, video installation, duration: 15:00. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Around the same time, I also learned the phrase “more than human” through the writings of Indigenous scholar Robin Wall Kimmerer. In an essay on linguistic imperialism and re-animating speech, Kimmerer writes that in Potawatomi language, “there is no it for nature… living beings are referred to as subjects, never as objects, and personhood is extended to all who breathe and some who don’t.” The term “more than human” elevates our non-human earthly companions and indicates our mutual entanglements with them. It is a recognition that reverberates through time and place, and posits that the landscape is not separate from us but deeply, inextricably, and complexly linked with our origins and our survival. [3]

An installation view of Mutual Terrain at RedLine Contemporary Art Gallery, curated by Adán De La Garza and Jenna Maurice, as part of Denver Month of Video (.MOV). Image by Madeleine Boyson.

It is with these concerns in mind that I first encountered Mutual Terrain at RedLine Contemporary Art Center this summer. The Denver Month of Video (.MOV) exhibition is curated by Adán De La Garza and Jenna Maurice and presents works that analyze the natural environment not “as a passive backdrop but as an active, animate force.” [4] As such, the exhibition questions Western tendencies to see land as disentangled from us, extractable by us, and profitable for us. By assembling only temporal multimedia in an otherwise sparse gallery flanked by working artist studios, Mutual Terrain reinforces the landscape as an active collaborator in anthropic endeavors, bringing the outside world to bear on the inside and disputing our arbitrary distinctions between the two.

Nika Kaiser (USA), Soft Slough, 2023, multimedia installation, duration: 8:43. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Visitors first meet Soft Slough (2023) by Nika Kaiser (USA) around the corner from the exhibition’s introductory text. The work features flora, fauna, and a half-moon mirror on the floor, floating wetland images in its dizzying, even nauseating, footage, meditative bubbles, and upside-down shots-within-shots. Alligators and other creatures from the American South replicate themselves on the wall and floor, even as the mirror’s edge cuts short these colorful images while they fold in on themselves.

Nika Kaiser (USA), Soft Slough, 2023, multimedia installation, duration: 8:43. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

A nearby Toshiba television produces staticky incoherence, and Kaiser’s total production revels in the possibilities inherent in dual and triaxial spaces like wetlands, where human and more-than-human beings may insulate themselves from “failing societal structures.” [5]

Ali Cherri (UAE/Lebanon), still image from The Digger, 2015, video installation, duration: 23:36. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Zooming out and contrasting wetland with desert nearby, Ali Cherri (UAE/Lebanon) presents The Digger (2015)—a 23-minute feature on Sultan Zeib Khan, a Neolithic necropolis caretaker in the United Arab Emirates’ Sharjah desert. Wide-angle shots combine with heat-soaked tilt-shifts and interior footage alongside digging, singing, and wind sounds to complicate Khan’s human figure relative to his arid surroundings. The word “necropolis” comes from the Ancient Greek, meaning an ancient and architecturally significant or monumental cemetery, but The Digger’s insistence on excavating the dead and flattening an otherwise overpowering scale instead shows where nature’s violences coincide with the ravages of human time.

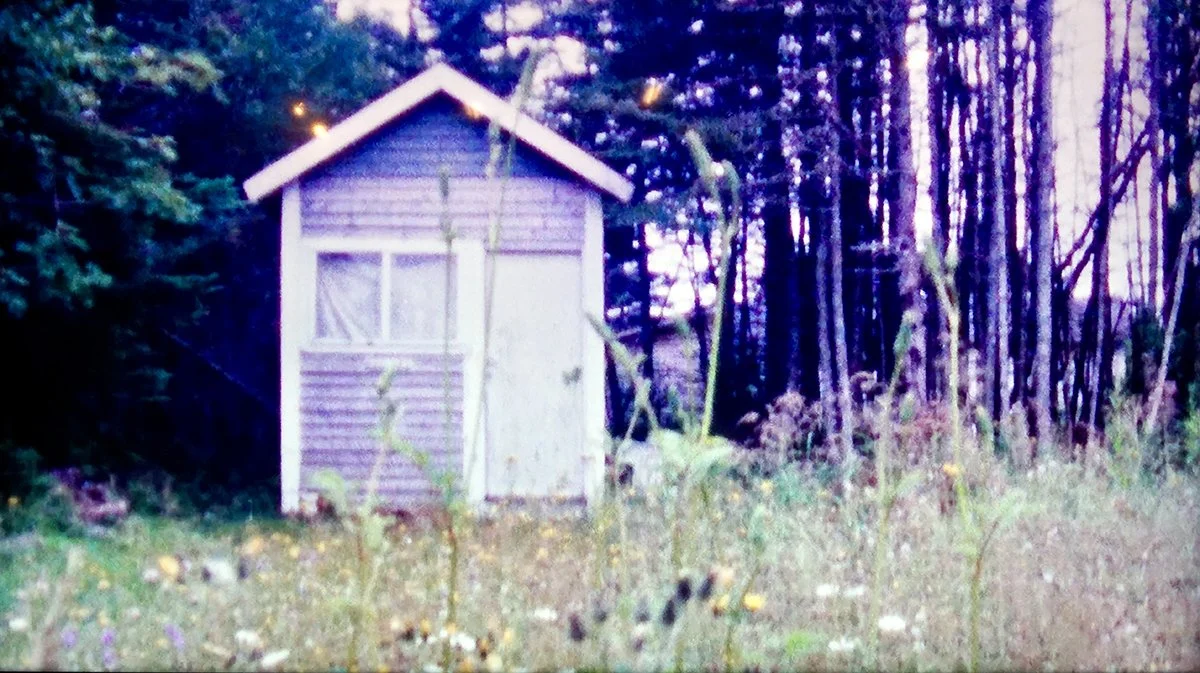

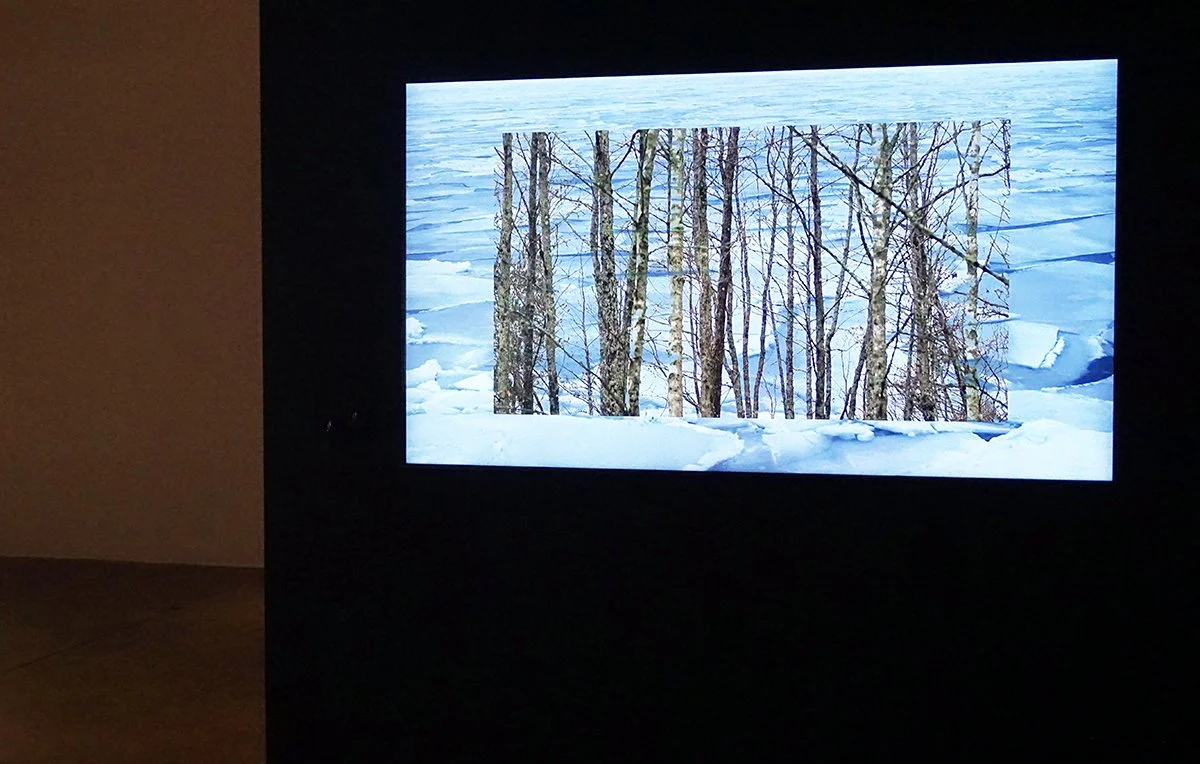

Ella Morton (Canada), still image from The Great Kind Mystery, 2022, video installation, duration: 15:00. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

On the other side of Cherri’s impersonal distance, Ella Morton (Canada) zooms in with The Great Kind Mystery (2022). This work is a 15-minute-long documentary about Newfoundland through the eyes of Inuk and Mi’kmaw artist Amy Hull, whose commentary accompanies Super 8-millimeter footage of Daniel’s Harbour.

Ella Morton (Canada), still image from The Great Kind Mystery, 2022, video installation, duration: 15:00. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Morton’s work is one of several in Mutual Terrain that require headphones, and which pulses with Hull’s narration while echoing the interpolated and filtered footage of her hometown on the Northern Peninsula. Beyond a significant need for a flash-warning, The Great Kind Mystery flickers emphatically between past and present, here and there, human and more than human.

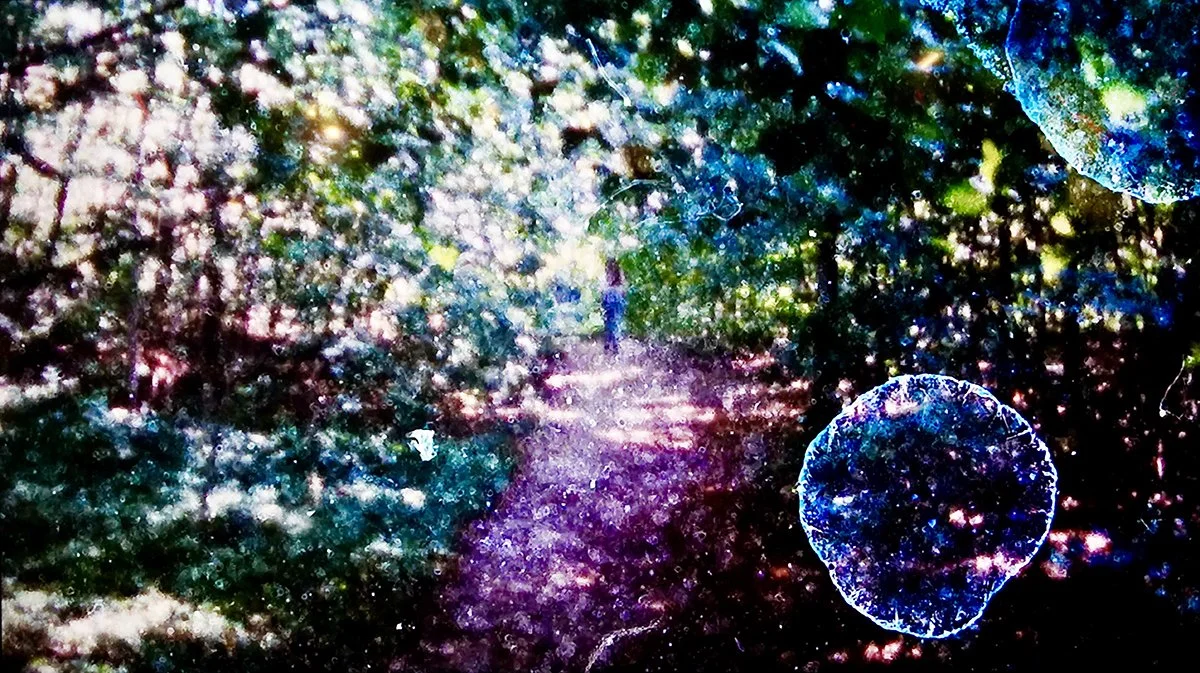

Felix Kalmenson (Canada), still image from A Line is Not a Line, 2015, video installation, duration: 10:55. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

In A Line is Not a Line (2015), Felix Kalmenson (Canada) similarly layers human with the more-than and the beyond human, extending the landscape to include technology in the form of Google Street View and Google Earth. With these databases as “contemporary analogs to colonial landscape painting,” A Line shows how our capricious borders influence ecology and smooth out a landscape “shaped by migration, extraction, and exploitation.”

Felix Kalmenson (Canada), still image from A Line is Not a Line, 2015, video installation, duration: 10:55. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Mirroring Cherri’s flatness, Kalmenson’s work highlights how technology allows us to reduce our surroundings and take less responsibility for them. When we measure each other with static images, A Line asserts, they become yet another tool of colonial violence.

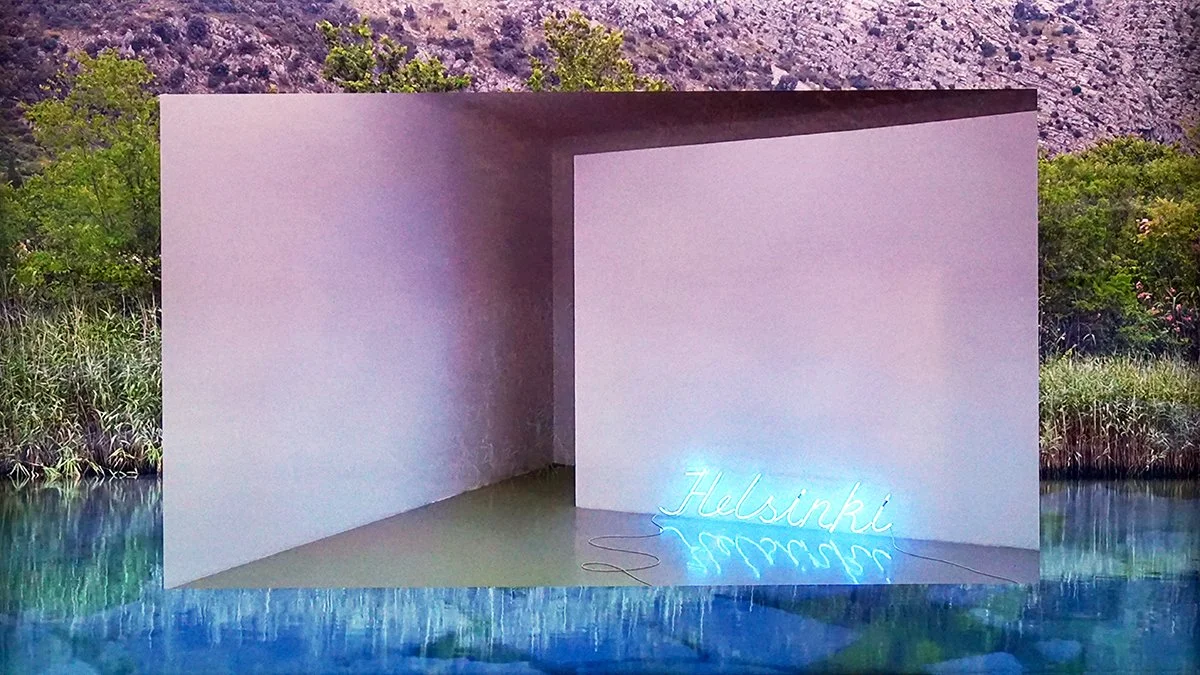

Nina Kurtela (Croatia), still image from Dear Aki, 2021, video installation, duration: 14:39. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Towards the back of the exhibition are the diminutive Dear Aki (2021) by Nina Kurtela (Croatia) next to Western Fronts: Cascade Siskiyou, Gold Butte, Grand Staircase-Escalante, and Bears Ears (2018) by Rick Silva (USA). The former squares the viewer in a conceptual space where names, nationalities, states, immigration status, and other politicized sites of the body intersect with location. Kurtela uses the 14-minute visual essay to send letters to Aki Kaurismāki, the Finnish film director and screenwriter, and to create fictional spaces inside extant ones.

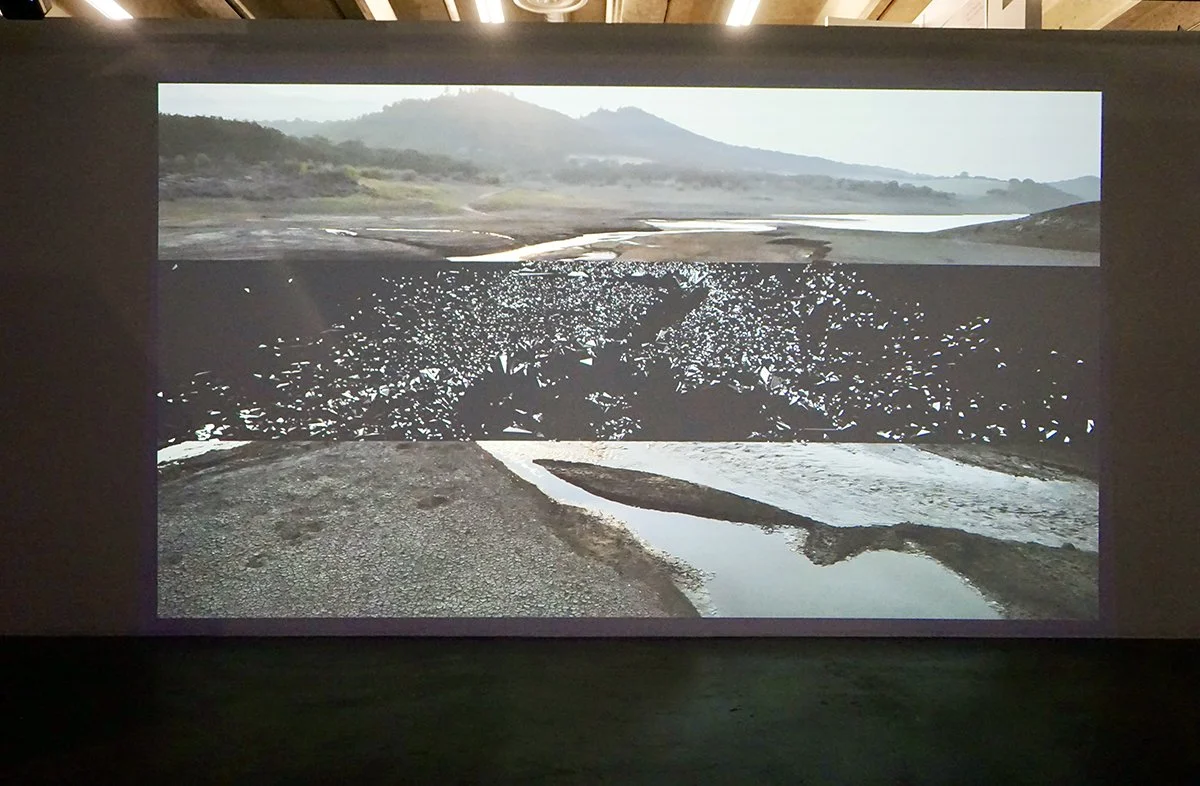

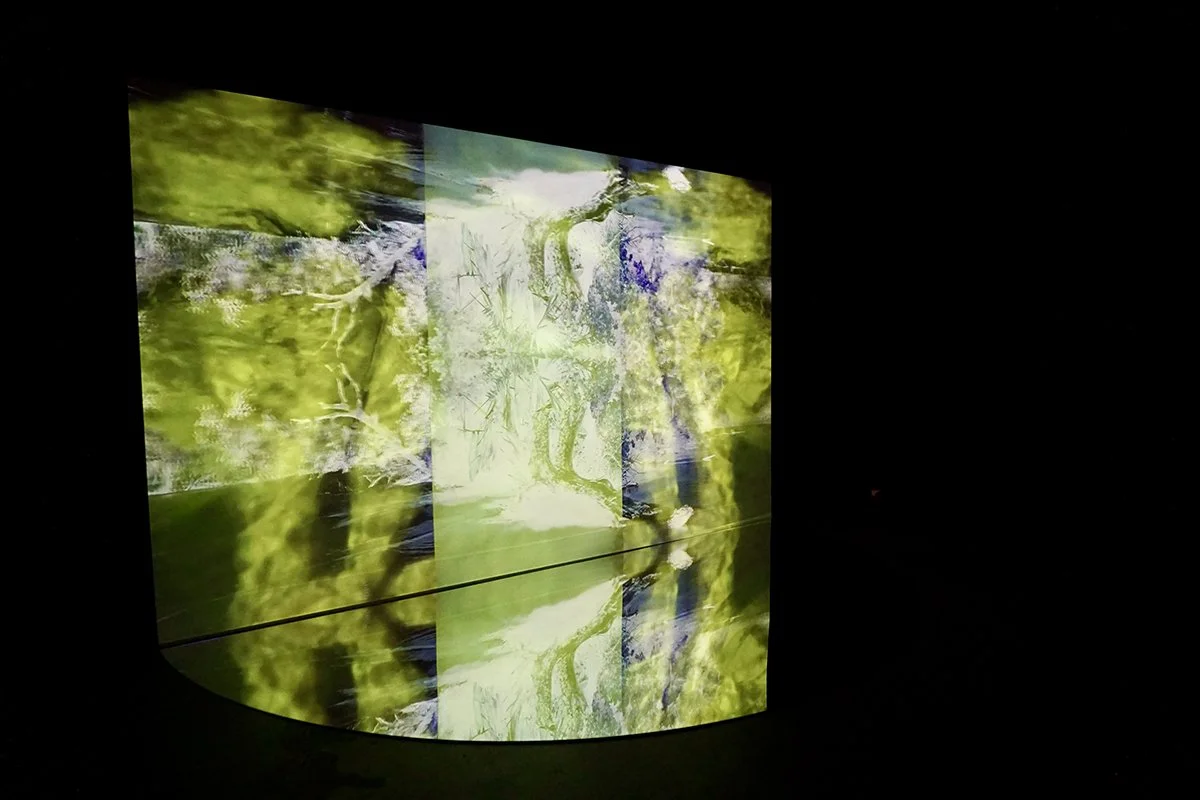

Rick Silva (USA), installation view of Western Fronts: Cascade Siskiyou, Gold Butte, Grand Staircase-Escalante, and Bears Ears, 2018, video installation, duration: 18:32. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

The latter artwork by Silva, however, contrasts Kurtela’s delicate and theoretical aria with a brash and oversized series of landscape shots. Silva interposes drone footage with three-dimensional animations of grayscale polygons which aim to “glimpse a near-future dystopia of computer-vision aided resource extraction.”

Rick Silva (USA), installation view of Western Fronts: Cascade Siskiyou, Gold Butte, Grand Staircase-Escalante, and Bears Ears, 2018, video installation, duration: 18:32. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

But while Western Fronts—the largest work in RedLine’s tall atrium—successfully recreates a land imperiled by human intervention, Silva’s approach remains heavy-handed, especially in light of Kurtela’s song-like pastels nearby.

Nina Kurtela (Croatia), still image from Dear Aki, 2021, video installation, duration: 14:39. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Overall, however, Mutual Terrain satisfactorily complicates human and more than human enmeshment. Curatorial requests to slow down and linger with each work are well rewarded and illustrate how anthropic entanglements in our natural world are less clear cut than they are continuously renegotiated relationships. Furthermore, the chosen works bolster De La Garza and Maurice’s intention to “form a collective meditation on interdependence” as they create an imitation landscape within the atrium and also converse with RedLine’s lit artist studios to the sides.

Nika Kaiser (USA), Soft Slough, 2023, multimedia installation, duration: 8:43. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

“I feel like I am a human being planting carrot seeds into Earth,” writes John Green in The Anthropocene Reviewed, “but really, as my brother would tell me, I am Earth planting Earth into Earth.” [6] Mutual Terrain sees us as Earth planting Earth, as part and parcel of our own environments, and as inseparable from the outcomes we constantly engender. It would be inaccurate, even dangerous, to ignore our species’ role in climate change and environmental devastation, but one benefit of Mutual Terrain is that visitors are invited to see the vast nuance inherent in what we do to the Earth—and thereby ourselves—while we are here. Nuance may be the key to our planet’s survival, and to keeping ecofascism violence at bay.

An installation view of Mutual Terrain at RedLine Contemporary Art Gallery. Image by Madeleine Boyson.

Be sure to see the exhibition and contemplate it all for yourself through August 3, 2025. Denver Month of Video will also conclude with several events during the last week of July. MOV will host a reception for Non-Playable at The STOREROOM on July 24; Summer Camp for Video Artist’s Big Exhibition Show: It’s Projecting a Big Hot Video Mess, Again and again and again and again and again and again and again and again and again and again and again at Squirm Gallery, and the opening of Under Pressure at Friend of a Friend on July 25; and a multimedia performance of Eclectic Systems for the closing night of .MOV on July 26.

Madeleine Boyson (she/her) is an Editorial Coordinator at DARIA and a Denver-based writer, poet, and artist. She holds a BA in art history and history from the University of Denver.

[1] Emmanuel Felton, “The Coronavirus Meme About ‘Nature is Healing’ Is So Damn Funny,” BuzzFeed News, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/emmanuelfelton/coronavirus-meme-nature-is-healing-we-are-the-virus.

[2] Alexander Menrisky is an assistant professor at the University of Connecticut and studies how environmentalism becomes part of personal and communal identity. Elaina Hancock, “A Darker Shade of Green: Understanding Ecofascism,” UConn Today, https://today.uconn.edu/2022/09/a-darker-shade-of-green/#.

[3] Robin Wall Kimmerer, “Speaking of Nature: Finding language that affirms our kinship with the natural world,” Orion Magazine, https://orionmagazine.org/article/speaking-of-nature/.

[4] From the Mutual Terrain curatorial introductory text. Denver Month of Video (.MOV) is a month-long, citywide exhibition and event series held every other year in July intended to showcase video-based art. See https://www.denvermov.com/ for a full listing of events, exhibitions, and screenings.

[5] This and all other unidentified quotes come from the exhibition texts.

[6] John Green, The Anthropocene Reviewed: Essays on a Human-Centered Planet (Dutton: 2021, 2023), 272.