Lasting Impressions / Onward and Upward

Lasting Impressions / Onward and Upward: Shark’s Ink

University of Colorado Art Museum

1085 18th Street, Boulder, CO 80309

Lasting Impressions: July 14, 2022–June 3, 2023

Onward and Upward: Shark’s Ink: September 6, 2022–July 15, 2023

Admission: Free

Review by Paloma Jimenez

Lasting Impressions and Onward and Upward: Shark’s Ink at the University of Colorado Art Museum present prints from an array of artistic movements to tell the idiosyncratic story of the United States. The works on view collectively assert that printmaking, long used as an accessible means for a wider audience to view an artwork or a message, pulses with an inherent urgency rooted in the desire for communication.

A view of the exhibition Lasting Impressions at the University of Colorado Art Museum in Boulder. Image by DARIA.

Dyani White Hawk, Wókağe | Create, 2019, from the series Take Care of Them, edition 2/18, screen print with metallic foil, 55.5 x 32 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Dyani White Hawk, Nakíčižiᶇ | Protect, 2019, from the series Take Care of Them, edition 2/18, screen print with metallic foil, 55.5 x 32 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

The front of the Lasting Impressions exhibition displays artworks exploring Chicano and Indigenous culture in the Western United States. Two complementary screen prints with metallic foil, Wókağe | Create and Nakíčižiᶇ | Protect (both 2019) by Dyani White Hawk, capture the celebratory detail work of her Lakota ancestors in graphically concise abstractions. Nearby, Rose B. Simpson, in Maria (2021), and Enrique Chagoya, in Road Map (2003) and Les Aventures des Cannibales Modernistes (1999), favor the instant legibility of iconography to mine the country’s history of natural resource exploitation and cultural erasures.

Alison Saar, Redbone Blues, 2017, intaglio on found vintage handkerchief, 17.5 x 16.875 inches. Image by DARIA.

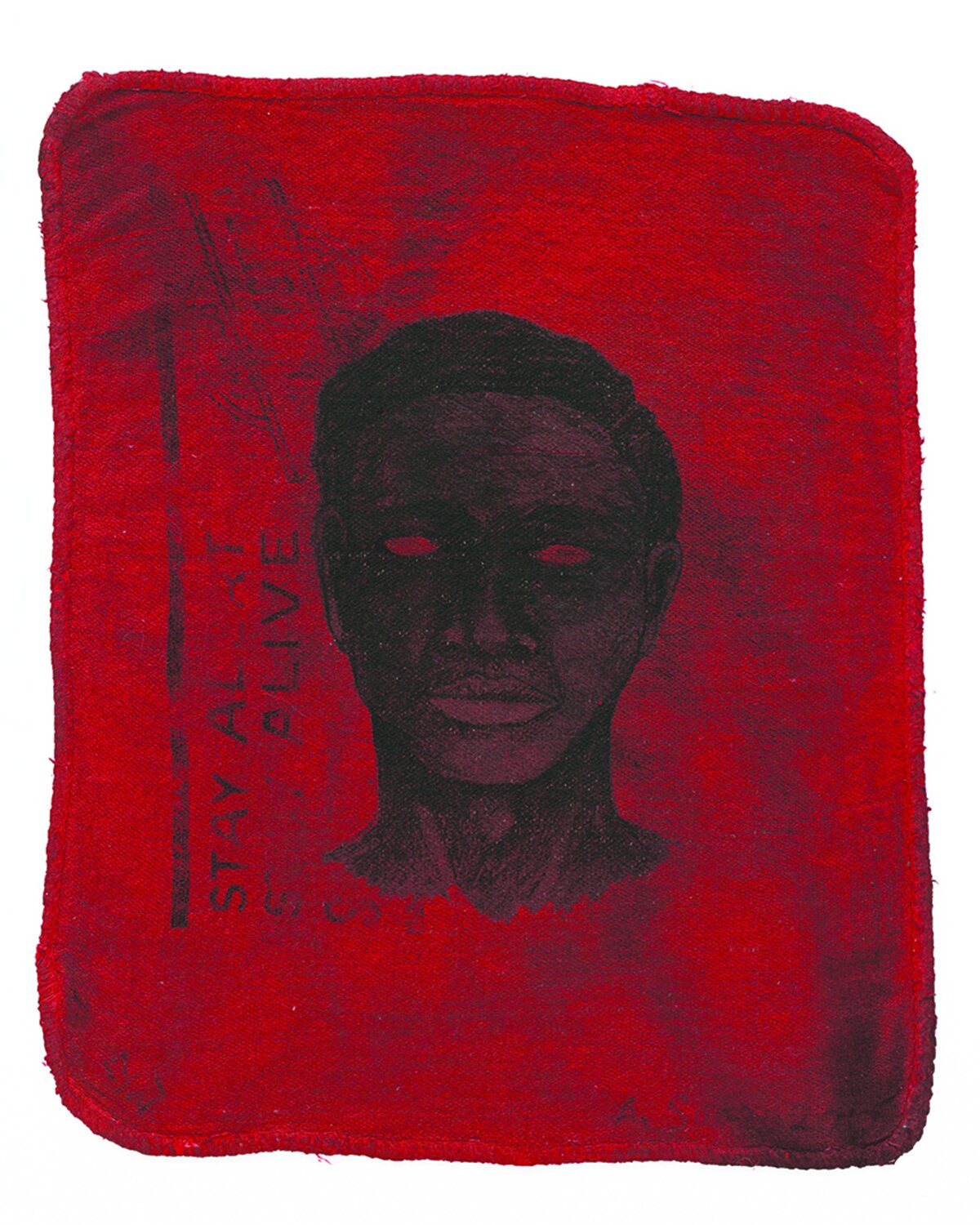

Alison Saar, Coal Black Blues, 2017, intaglio stained cotton shop rag, 17 x 13 inches. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of the CU Art Museum, University of Colorado Boulder.

On the opposite wall, artists push materially inventive printmaking techniques to depict the evolving narratives of Blackness. Alison Saar’s emotionally haunting intaglio prints on found pieces of textile (Redbone Blues and Coal Black Blues, both 2017) evoke the story of the Veil of Veronica, in which the image of Jesus appeared on a cloth after sweat and blood were wiped from his face. Saar’s tender portraits are not religious relics, but rather relics of the emotional and physical labor Black people have performed throughout America’s violent past.

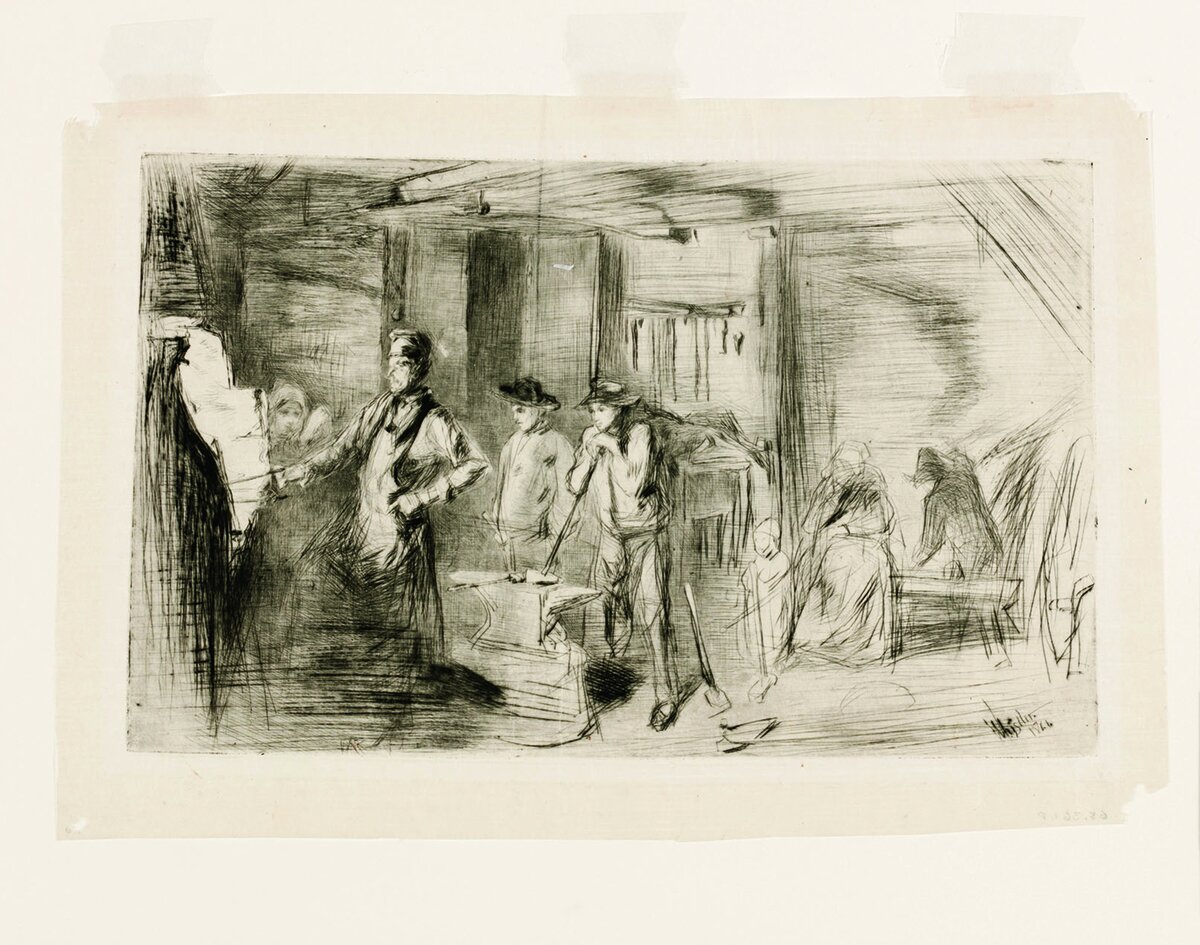

James McNeill Whistler, The Forge, 1861, printed later, fifth state of six, drypoint, 7.75 x 12.25 inches. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of the CU Art Museum, University of Colorado Boulder.

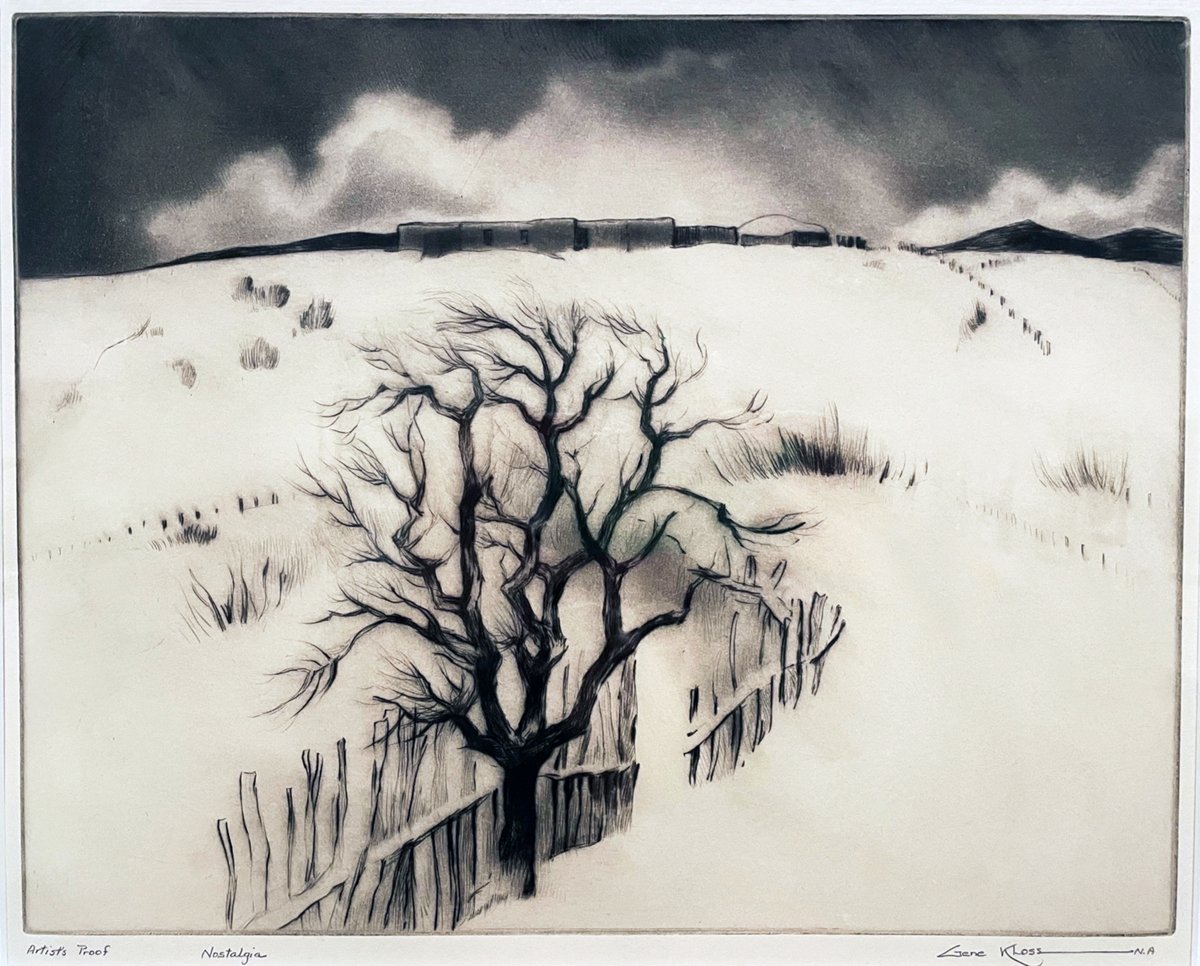

Gene Alice Kloss, Nostalgia, 1973, drypoint and aquatint, 10.875 x 13.875 inches. Image by DARIA.

Other artists in the collection delve into the sublimity of everyday American scenes. The Forge (1861) by James McNeill Whistler, with its tornado of linework and swiftly rendered figures, seems etched out of the hot irons it depicts. Gene Alice Kloss’ aptly named Nostalgia (1973) finds contemplative beauty in the stillness of a forlorn tree. Bits of fragmented, inky black plants punctuate the surrounding white expanse.

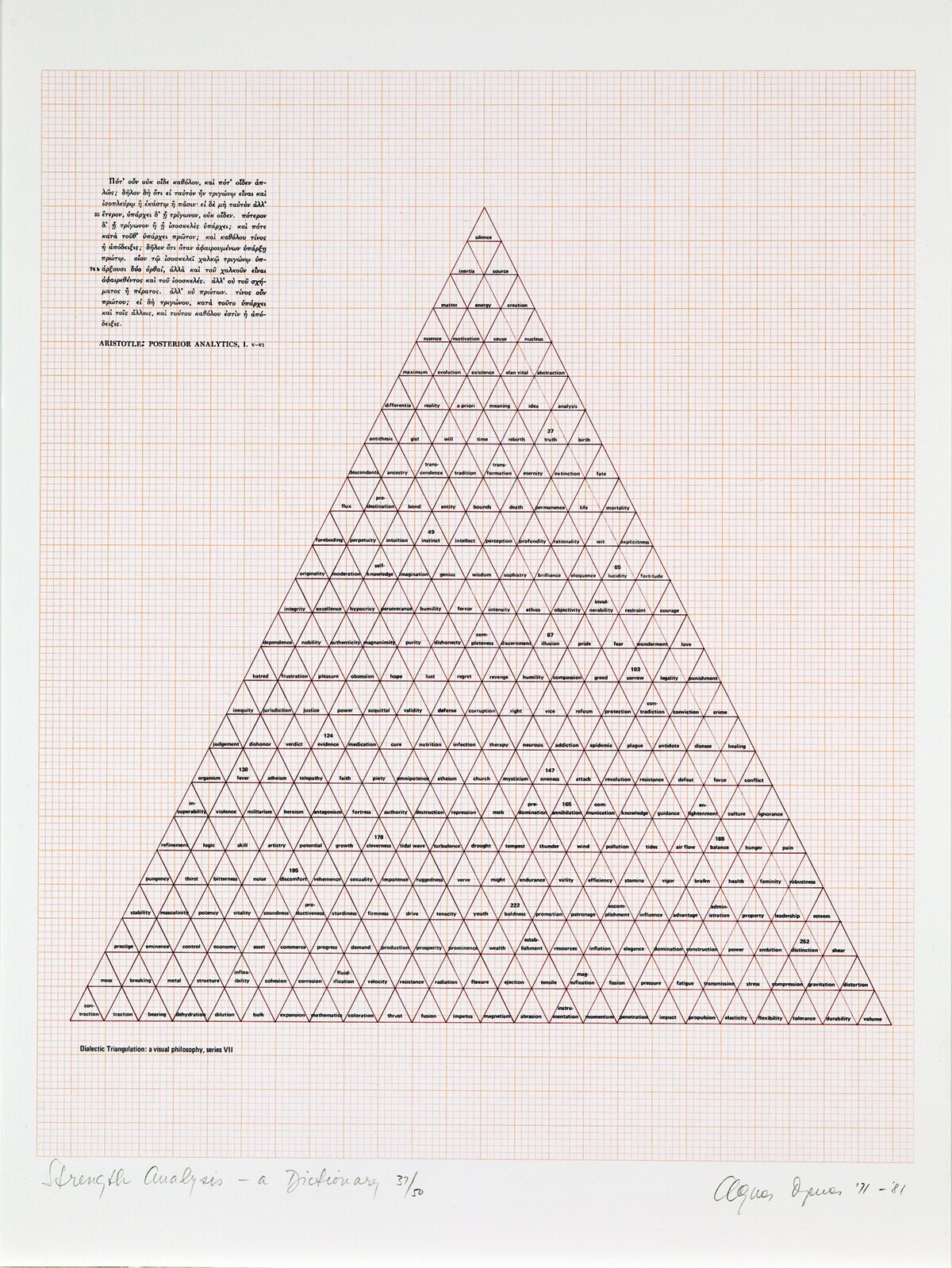

Agnes Denes, Strength Analysis - A Dictionary of Strength, 1971-81, lithograph, edition 37/50, 23.25 x 17.5 inches. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of the CU Art Museum, University of Colorado Boulder.

A detail view of Agnes Denes’ Strength Analysis - A Dictionary of Strength, 1971-81, lithograph, edition 37/50, 23.25 x 17.5 inches. Image by DARIA.

The clarity of black and white printmaking is a natural choice for the conceptual works in the collection. Sol LeWitt, Frank Stella, and Bruce Conner encounter philosophical truths in repeated linework. Strength Analysis - A Dictionary of Strength (1971-81) by Agnes Denes maps out the many words associated with strength to construct a seemingly perfect pyramid, strong enough to hold the enormity of her semantic endeavors.

Elizabeth Murray, Snake Cup, 1984, lithograph, 32 x 25 inches. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

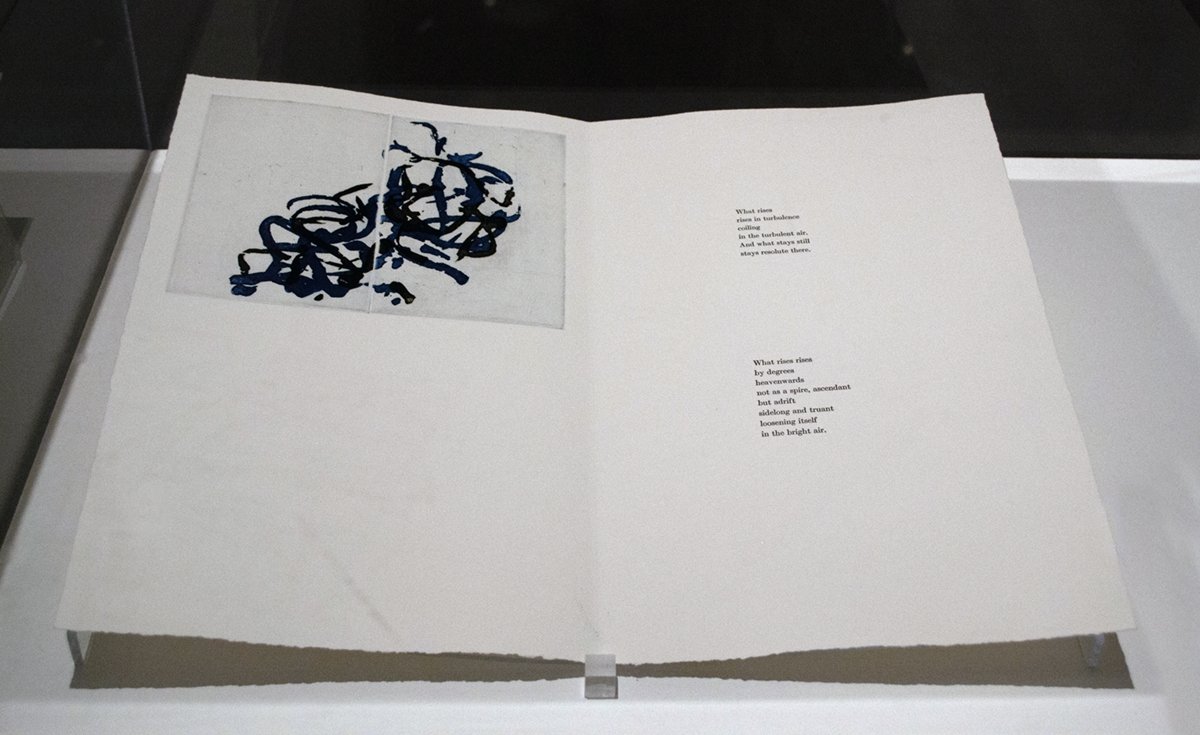

Joan Mitchell, Smoke, 1989, illustrated book with sugar-lift and spit bite aquatints, each page 14 × 9.0625 inches. Image by Paloma Jimenez.

Another grouping boasts the joyous cacophony of abstract art in America. Included are prints created by artists generally known for working on larger scales, such as Helen Frankenthaler and Clyfford Still; here viewers are granted a glimpse into their more spontaneous ideas. Elizabeth Murray’s lithograph Snake Cup (1984) jumps out of the wall with a welcomed riot of acid green and electric pink. Her gestural marks careen around the paper with a looseness not often associated with printmaking. Joan Mitchell, uniquely equipped for composing elegantly grotesque poetry with paint, also makes an unexpected appearance. In an intimate page from her illustrated book, Smoke (1989), language coexists with scrawling inkwork.

An installation view of the exhibition Onward and Upward: Shark’s Ink at the University of Colorado Art Museum in Boulder. Image by DARIA.

Lasting Impressions reads as an anthology of the United States told through artists’ hands, utilizing printmaking as an indispensable tool for thought exchange. The link between creation and communication continues in the adjacent exhibit, where Onward and Upward: Shark’s Ink assembles works from the recently acquired “Sharkive,” a treasure trove of editioned prints and production materials from numerous artists who have worked with Shark’s Ink—a contemporary print publishing atelier near Lyons, Colorado—over the past 46 years.

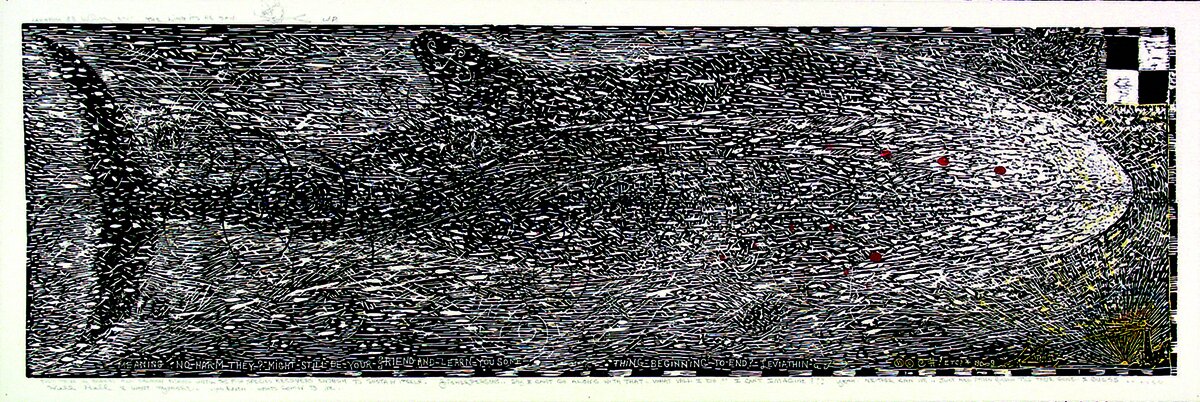

William T. Wiley, Leviathan II, 1992, working proof, hand-colored woodcut on white Rives BFK paper, 26.375 x 78.5 inches. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of the CU Art Museum, University of Colorado Boulder.

In rarely publicized evidence of the creative process, the art proofs and printing blocks on view celebrate the equally calculated and spontaneous journey of creating a print. The artist’s proof of Leviathan II (1992) by William T. Wiley simmers in frenetic limbo. Symbols somewhere between a censored swear word and a computer generated password are hacked into the bottom right corner where a city sun rises under a looming sea creature. Wiley is a natural choice to collaborate with Bud Shark, as they each find themselves embedded in the cultivation of a distinctly American brand of folklore.

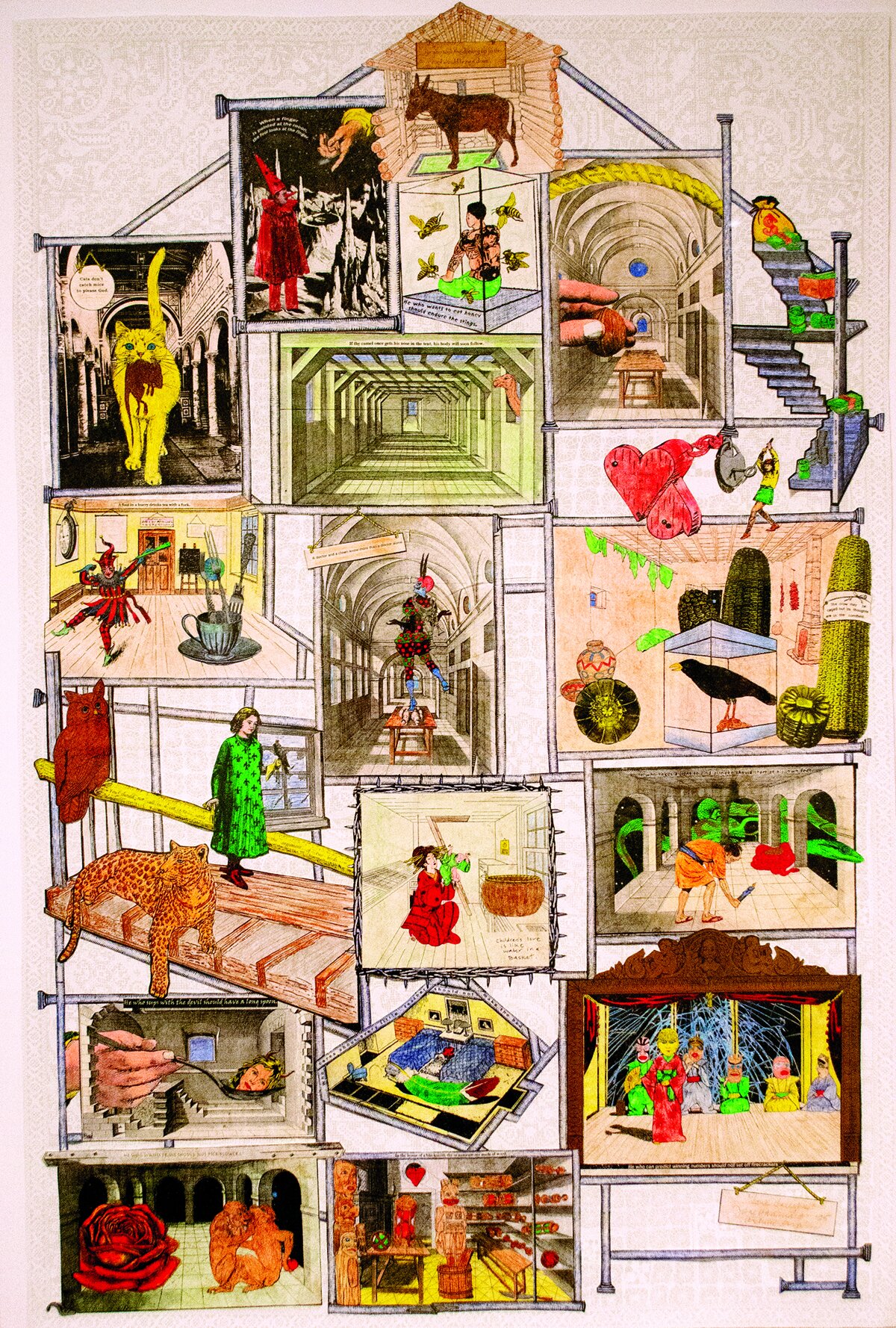

Jane Hammon, Love Laughs, 2005, color lithograph with colored pencil and collage on Rives BFK, amate, and Thai mulberry papers, 51.25 × 33.75 inches. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of the CU Art Museum, University of Colorado Boulder.

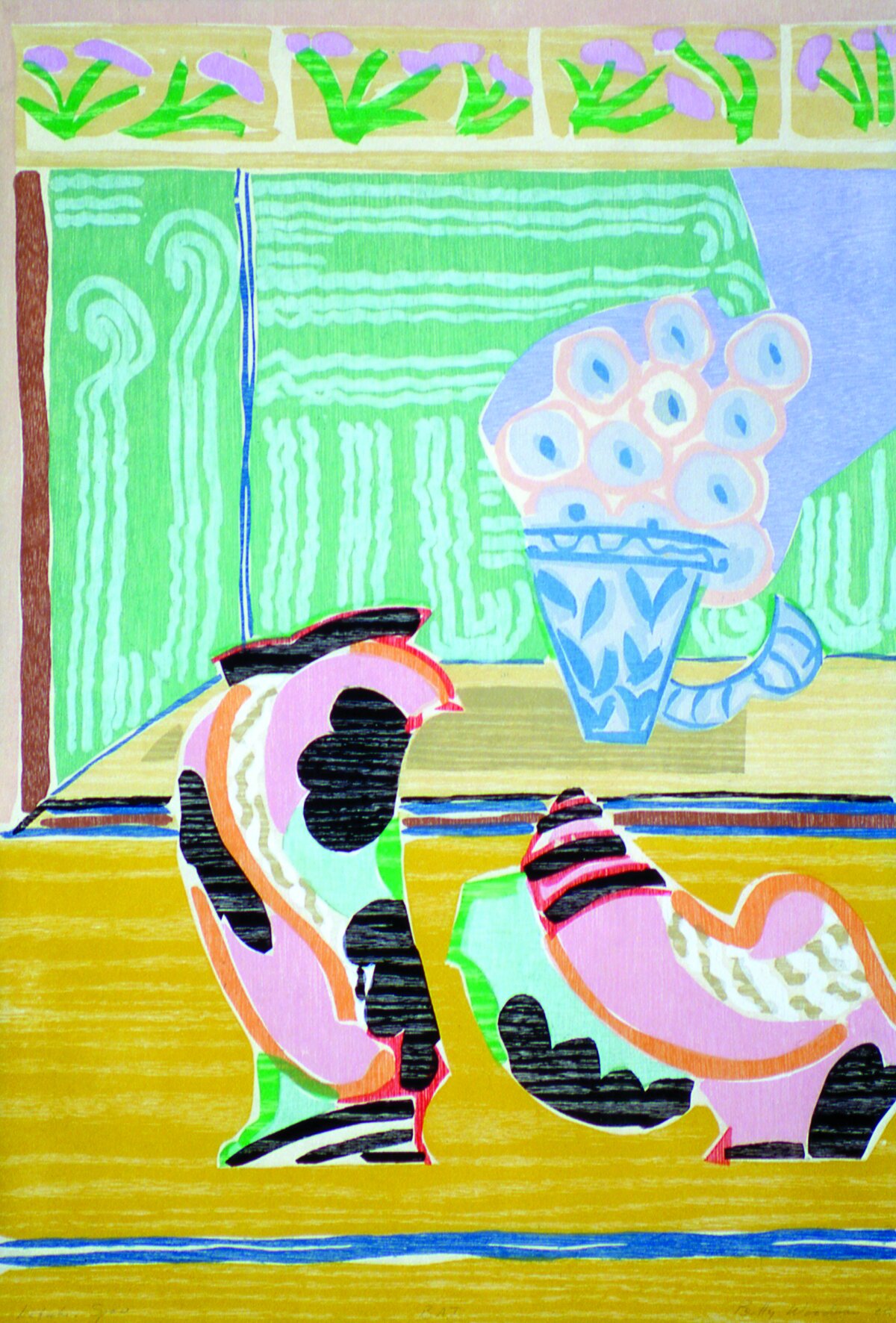

Betty Woodman, Kabuki Space, 2000, color woodcut on natural Thai mulberry paper, 37 x 25.25 inches. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of the CU Art Museum, University of Colorado Boulder.

For all the planning that goes into preparing a plate or block, the ability to create multiples leaves room for more impulsive moves and the possibility of stumbling upon a magic mistake. Jane Hammonds plays with the multiplicity of language in a grouping of Love Laughs (2005) prints. Visual puzzles gleaned from different cultures float inside the rooms of a dollhouse and each color variation provokes a new reading of the piece. The segmented process of printmaking is well suited for depicting the changing depths of interior spaces, a subject also explored by Betty Woodman in Kabuki Space (2000). Her masterful woodcut print glows with all the diaphanous colors of a fruit bowl in the morning haze.

Tom Burckhardt, Workshop, 2004, color lithograph on white Rives BFK paper with chine collé linocut on blue and pink Yamamoto and green Thai Chiri papers. Image by Wes Magyar, courtesy of the CU Art Museum, University of Colorado Boulder.

Artists who work with Shark’s Ink find humor and narrative in a well chosen color. Tom Burckhardt uses mustard yellows and candy apple reds to delineate the curves of a landscape composed of the various tools and shapes in Workshop (2004). The entire scene seems ready to drop out of the frame and down onto the floor, ink splattering, tools clattering.

Red Grooms, Little Italy, 1989, color lithograph on white BFK paper, cut, assembled in three dimensions with glue in Plexiglass case, working proof 3/5, 27 × 38.5 × 16.75 inches. Image by DARIA.

Red Grooms takes humorous illusion into three dimensions with his Little Italy (1989) lithograph, which is cut out and glued together to create a dioramic street view. It is a clever reinvention of a pop-up book; the multilayered tactility of the image captures the cramped streets of New York better than any other format could. Bud Shark’s workshop exists as a lively watering hole for those with a double dose of curiosity and a sly disregard for tradition.

An view of Onward and Upward: Shark’s Ink at the University of Colorado Art Museum in Boulder. Image by DARIA.

The University of Colorado Art Museum’s print collection is complex, unpredictable, and vital; it continues to evolve much like the America it depicts. Lasting Impressions explores the long history of printmaking in the United States, while Onward and Upward: Shark’s Ink infuses the collection with a localized dose of contemporary energy. Both exhibitions celebrate printmaking as a collaboration between technical expertise and artistic vision.

Paloma Jimenez is an artist, writer, and teacher. Her work has been exhibited throughout the United States and has been featured in international publications. She received her BA from Vassar College and her MFA from Parsons School of Design.